[This is a shorter version of our full consumer guide on navigating the facts-optional world of social media.]

Information comes at you so fast on social media that it’s hard to know what to believe.

As social platforms like Facebook, Twitter and TikTok, and private messaging platforms like WhatsApp and Telegram, have become central parts of everyday life in the U.S., falsehoods have flourished and our democracy has been weakened by an inability to agree on facts.

Though we all play a part in amplifying falsehoods online, it’s not up to you to clean up the internet. Social platforms will continue elevating emotional posts. Bad influencers will keep spewing toxic content.

But there are some actions you can take now that can help blunt the reach of misinformation. And if you’re willing to help family and friends better understand what they’re seeing online, you’ll also be sticking up for the truth.

- Assess credibility

A lot of people believe there’s real news, and “fake” news, and nothing in between. But it’s not so simple. Effective disinformation usually contains a kernel of truth.

Facts are often cherry-picked and spun to suit political and ideological motives — and to make money. Funders of shady news websites, special interest groups, and bad actors hocking phony nutritional supplements all stand to profit.

Here’s how to tell if something’s trying to fool you:

If you can’t tell who wrote an article, that’s an immediate red flag. Some stories are written by an editorial team and will be credited as “staff report” or something similar. But most news stories credit a reporter or two.

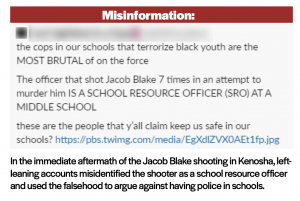

What was true a year ago may not be true now. When you open an article, check to see when it was published. The date should be at the top, near the author’s name. While some content is totally made up, it’s increasingly common to see reality-based photos and articles used out of context — usually, old ones presented as if they’re new.

If you’re suspicious of a claim made on social media, don’t take your former roommate’s word for it — search it yourself. Look for primary sources of information and check the underlying claim. In your searches, avoid loaded terms like “exposes,” “hoax” or “uncovers” and use neutral phrasing instead, such as “where to vote” or “vaccine information.” Be especially wary if the content has been captured in a screenshot, and doesn’t include a link to supporting evidence.

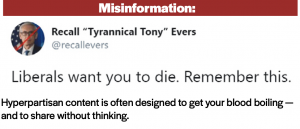

Inflammatory, provocative and loaded language is a sign that the source isn’t credible. So is an ALL-CAPS RANT with lots of punctuation mistakes and exclamation marks! Strange, off-putting and disturbing photos are another warning sign.

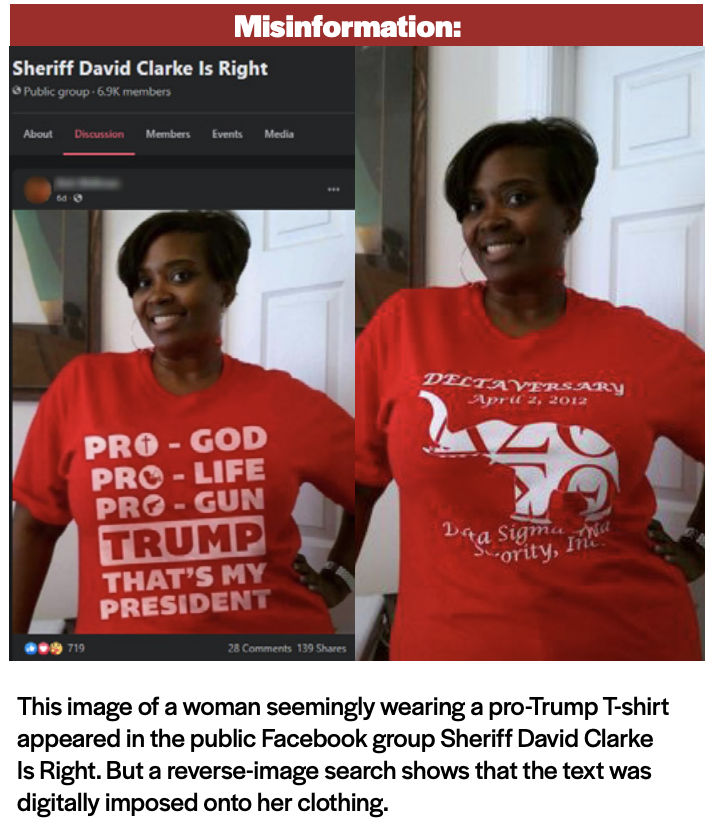

Running a reverse-image search to see all the places an image appears online. Right click the image, save it to your desktop, and upload it to a tool like TinEye.

- Go straight to the good stuff

An alternative to struggling to control the firehose of misinformation that is your social media feed: Just turn it off. Knowing where to find good information is critical. Here’s how to do it:

Checking out a news organization? Look at who’s on staff, how it’s funded, and where it’s based. How many people are involved? What are their credentials?

Don’t confuse opinion pieces with news reporting. Opinion pieces show what an individual person thinks about something and doesn’t necessarily reflect the view of the reporters in the newsroom.

In a good news organization, there is a dividing line between an organization’s news coverage and the opinion pieces it runs. Reporters try to draw conclusions from facts but don’t express opinions.

Good sources don’t ask you to trust them, they show why you should.

- Think twice before sharing

Since social media algorithms elevate posts with emotional content, disinformation is amplified by strong reactions — usually negative ones. Social platforms encourage people to glance at stuff, react emotionally, and share it right away. And they’ve been flooded with rumors, conspiracies and hoaxes designed to get your blood boiling.

If something makes you angry, fearful or anxious, don’t click “share” right away, and don’t compose a scorched-earth hot take. Despite what you’ve been encouraged to do, nobody’s waiting for you to share this meme or that article.

This applies beyond outrage. If content makes you feel emotionally or intellectually validated, stop to consider whether it was designed for that purpose.

If you come across an attention-grabbing headline, don’t just pass it along. Click the link, read the article, and know what you’re sharing. If you’re uncertain, don’t share it at all.

Propagandists would have us believe that nothing can be trusted. Don’t fall for that mindset. Navigating the social web requires emotional skepticism. But that doesn’t mean throwing up your hands and giving up, or becoming a hardened cynic.

In the end, social media adds layers of filtration that muddy a person’s understanding of the news. You don’t need friends, family or Facebook algorithms interpreting what’s important. Go right to reputable sources instead.

- Fact-check people you know

We’ve all been there: Your friend, father or elected representative shares an article pushing the Pizzagate conspiracy on Facebook, or goes on a Twitter diatribe about how COVID-19 contact tracers are spying on them. (They aren’t.)

Research shows that you should speak up, even if it isn’t easy. Here’s how to fact-check people you know without burning bridges:

Before jumping into the conversation make sure the content you’ve seen is actually false. Do your own homework first.

Remember that most people don’t spread falsehoods on purpose. Be civil if you offer a correction — especially if it’s directed at a loved one.

Whether to offer your correction with a public comment or a private message is worthy of consideration. Making the correction public helps other people viewing the content to see that it may be false. On the other hand, nobody likes feeling duped, and a call-out could invoke a defensive posture, or an argument that could amplify engagement with the post.

Acknowledging that everyone – including yourself – is susceptible to misinformation can be helpful. Talk about a time that you were fooled by a viral image or a fabricated news story.

Link to expert sources. While this isn’t foolproof – much of the public no longer trusts government and media institutions long considered to be unbiased sources – it’s part of doing your homework.

Don’t restate the falsehood. Repetition is essential to persuasion, so start and finish your correction with the truth. If somebody else has already offered an accurate correction, go ahead and give one, too.

Rather than simply telling somebody they’re wrong, explain why something is untrue. Give the full narrative version with as much explanatory detail as you can provide.

Emphasize that people are entitled to their opinions, but facts still matter. Remind them that we should all care about the truth.

And finally, know when it’s a lost cause. If someone is really digging in their heels, or the conversation is escalating from constructive to combative, find a delicate way to extract yourself.

The Election Integrity Project is a nonpartisan initiative of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism and the Center for Journalism Ethics at UW–Madison in collaboration with First Draft and with the support of Craig Newmark Philanthropies.