In early October, I found myself wanting to better understand the Israel-Hamas War and was leery of social media feeds where carefully constructed algorithms are designed to fuel opinions over fact. So I turned to The New York Times, as I often do when looking for more reliable information, and was quickly greeted by the suggestion to drink wine from Portugal.[1]

My experience was not some kind of digital anomaly. If you scroll down an article on nytimes.com, you’ll likely see a bolded heading “Editor’s Picks” encouraging you to explore more content on the site. For me, the editors seem to have selected an advertisement for wine. These news suggestions from New York Times editors appears almost inconspicuously alongside an important news story— one that I had sought out to better understand the complex history of two politically fraught regions.[2] The ad’s near-natural presence is what makes it so powerful; it blends seamlessly into the architecture of the page encouraging eyeballs to miss cues that it is an ad at all. The optics reveal the problem with journalism’s battle between its visible and invisible ethics. On the surface, ethical handbooks and codes of conduct sound sensible and noble, but in practice they are contradicted in plain sight and in ways that are easy to miss.

As a field, journalism continually negotiates its connection to the historical norms and values of news production while ever-changing pressures of news-delivery mediums make visible a new set of values and tensions. Ethics are never a product of one meeting or a reflection of a single point in time — just like no one ad for wine defines The New York Times’ standards. Rather, ethical values are created and constantly reinforced by culture, societal norms, economic pressures, legal and regulatory conditions as well as technology. If you visit The New York Times’ Ethical Journalism Handbook, here’s what you’ll see today:

The relationship between The Times and advertisers rests on the understanding, long observed in all departments, that news and advertising are strictly separate — that those who deal with either one have distinct obligations and interests and neither group will try to influence the other.

Yet The Times’ statement is demonstrably false, both today and historically. Alongside writing that brings to the fore the brutality of war— killings— readers are encouraged to learn how wine in Portugal pairs so especially well with food. Here, the paper violates its own ethical handbook to keep advertising and news separate while disregarding SPJ’s code to be transparent and act independent of commercial interests.

Contradicting an ethical code of conduct need not be reprehensible; it can even be a desirable act under the right circumstances. The New York Times isn’t a nonprofit news organization and, as such, it isn’t exempt from commercial pressures. The money it gets from advertising wine can help fund a wide variety of things: new games, investigative journalism, crossword puzzles, video production and many more items that readers find valuable. Times sales staff also use profits to take advertising clients out to dinners in an effort to secure more business to pay for more journalism.

The contradiction of ethics is also reflected by the language used to describe the practice of carefully threading commercial messages—like the wine ad— into journalism. Terms like “branded content” and “native advertising” are defined by marketing practitioners and academics as a type of advertising that mimics the style and format of the platform in which it is inserted, such that it appears “native” to the social media feed or editorial content it surrounds.[3] When commercial messages appear native to a channel that is trusted to provide independent news, that practice violates the ethics journalists claim to hold dear. Natively placed ads are the opposite of a publisher acting transparently or being independent and accountable. Peer-reviewed research shows that even if a native ad has a disclosure label— common terms are “paid post,” “sponsored content,” “branded content,” “partner content”—a majority of people miss the label entirely.[4] A 2016 study published in American Behavioral Scientist showed that more than 30 percent of readers of a sponsored news story never even glanced at a disclosure label when it was there.[5] The same study found less than one in five participants recognized the article as advertising. The labels might as well have been invisible to the majority of readers who gazed over the content.

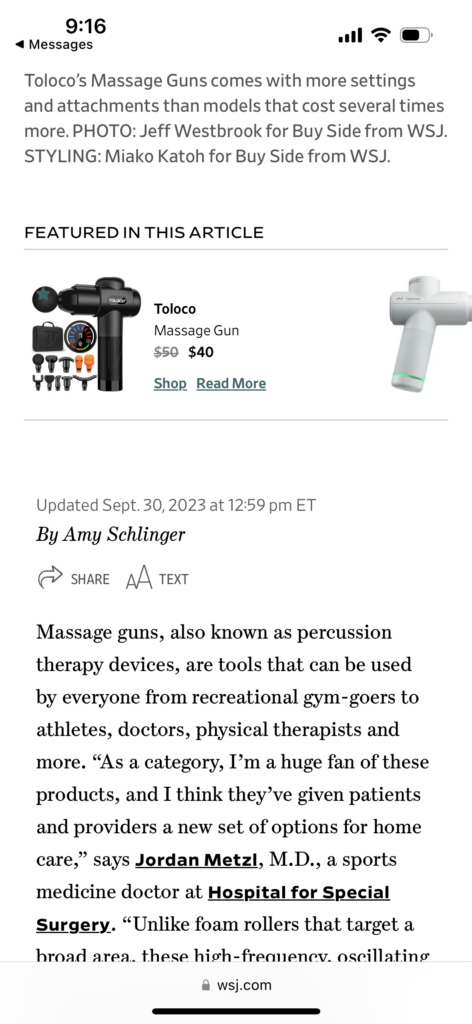

These ethical violations are also present in similar legacy or mainstream newspapers like The Wall Street Journal (WSJ). As I was recently catching up on news on the subway, WSJ had a new muscle massage device recommendation for me, and I was eager to learn about it as someone who enjoys HIIT workouts. But it took me—someone who is writing a book on invisible ads—several minutes to confirm the seeming article was, in fact, an ad. It wasn’t labeled as an ad in the news grid I was scrolling through and then I kept seeing mention of “Buy Side from WSJ.” After more investigation, it became clear that the “Buy Side” is another channel WSJ uses to secure ad dollars. In the lightly grayed out “advertiser disclosure” text I clicked on, WSJ writes: “Compensation may influence the way our advertising partners rank offers within a comparison table or advertising unit, but does not influence our editorial content.” More digging led me to @BuySideWSJ’s X (previously Twitter) handle bio: “Shopping and money advice you can trust. Separate from @wsj newsroom—they are the news side, we are the buy side. We might earn commission from clicking links.” For any reader to spend time getting to the bottom of what counts as an ad, how exactly it is labeled, and created is the opposite of transparent— it is obfuscation through deliberate and profitable calculation.

The Ochs-Sulzberger family controls about 91 percent of The Times’ and this ownership elects 70 percent of the company’s board members.[6] As a result, The Times is somewhat protected from the marketplace. While it is a publicly traded company, a family, not Wall Street, still owns it. This extra layer of protection makes The Times less susceptible to activist investors who can buy enough shares of the paper to control and restructure its business. The fear is wholly reasonable with Jeff Bezos completing his decade-long ownership of The Washington Post (purchased in 2013). The Times’ family structure makes the company’s actions even more noteworthy, and thus more disturbing, because it doesn’t have the same pressures to make money as The Wall Street Journal, owned by Rupert Murdoch.

In 2014 when I started researching invisible ads, advertising revenue was more lucrative than profit generated from subscriptions. Today, the equation has flipped with The Times’ digital ad revenue coming in at $61.3 million in Q1 2023, due to a decline in revenue from creative services— including native ads—according to the company.[7] The Times’ digital-only subscription revenue is up 14.1 percent to $258.8 million.[8] The flip from an advertising-driven profit model to a subscription-led one may seem surprising, but the success of one is dependent on the other. Your subscriptions feed the advertising beast — your data and time is what’s most valuable to further sell native and regular advertising.

Both The Times and WSJ hold the reputation and trust readers place in them as sacrosanct. Trust, transparency and independence are ethics that are plainly visible on their respective website missionstatements. What isn’t visible is the degree to which the profit motive of news publishers is invisibly shaping their ethics behind the scenes—you can’t supervise what you can’t see.

Ethics are theoretical when expressed through writing and become concrete when conveyed through action. Journalism’s first code of ethics was penned in 1910 by W. E. Miller of the local Kansas paper, St. Mary’s Star; it not only condemned publishing fake interviews and facts but it also had many rules about advertising’s place in news. Under the headline “Responsibility,” W.E. Miller writes: “The authorship of an advertisement should be so plainly stated in the context or at the end that it could not avoid catching the attention of the reader before he has left the matter.”[9] The code calls for all advertisements in the news columns to be followed by the word “advertisement” or its abbreviation. More than a century later, news outlets still struggle to follow common sense ethical codes.

Journalism ethics codes emerged as a response to concerns about sensationalism, propaganda and the need for reliable information in the early 20th century. The values we associate with journalism are a byproduct of reporters trying to professionalize their craft amid the rampant yellow press. Objectivity as a professional practice became a device for staying reliable in a world of skepticism, a world where all communication was colored by the interests it represented.[10] Adolph Ochs bought The Times in 1897 when it was struggling financially and grew its readership by launching a branding campaign. Ochs put “All the News That’s Fit to Print” on the front page of the paper. The Times wanted to establish itself in a different category altogether. As the scholar Michael Schudson has written, “It pointedly advertised itself with the slogan, ‘It does not soil the breakfast cloth,’ as opposed to the ‘yellow’ papers that sensationalized facts.”[11] Sure enough, The Times’ readership steadily increased; within a year its circulation jumped from 25,000 to 75,000. Ethical codes can be profitable in the right environment.

Today, the highly visible ethical codes and statements remain a marketing tactic not dissimilar from Ochs’ iconic branding campaign. What is left invisible is how much these ethical codes are lived, without average watchdog citizens digging into grayed-out text running alongside news articles to learn where commercial pressures may compromise independent news coverage. This challenge of press independence is hardly new as history teaches us, but history also underscores the importance of holding news publishers accountable for the vital role they play in supporting a healthy information ecosystem.

Ava Sirrah is a professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business. This article is based on research from her forthcoming book, Invisible Ads: How Marketers Shape Our Information Economy, which will be published by MIT Press in 2024. She is passionate about helping universities update their curriculum to address contemporary challenges in our media ecosystem. Her consulting firm, Ivory Field, provides educators with case studies and lesson plans that address real-world problems to better prepare students for jobs in the media.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/13/world/middleeast/israel-hamas-war-mideast.html

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/13/world/middleeast/israel-hamas-war-mideast.html

[3] Mara Einstein. Black Ops Advertising: Native Ads, Content Marketing, and the Covert World of the Digital Sell

[4] Wojdynski, B. W. (2016). The Deceptiveness of Sponsored News Articles: How Readers Recognize and Perceive Native Advertising. American Behavioral Scientist, 60(12), 1475–1491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764216660140

[5] Wojdynski, B. W., & Evans, N. J. (2016). Going native: Effects of disclosure position and lan- guage on the recognition and evaluation of online native advertising. Journal of Advertising, 46, 157-168.

[6] Ember, Sydney. “A.G. Sulzberger, 37, to Take Over as New York Times Publisher.” The New York Times, 15 Dec. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/12/14/business/media/a-g-sulzberger-new-york-times-publisher.html.

[7] https://nytco-assets.nytimes.com/2023/08/Q2-2023-10-Q.pdf

[8] https://digiday.com/media/media-briefing-a-mixed-first-quarter-for-publishers-ad-revenue/

[9] “Code of Ethics for Newspapers Proposed by W. E. Miller of the St. Mary’s Star and Adopted by the Kansas State Editorial Association at the State Convention of the Kansas Editorial Association, March 8, 1910.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 101, 1922, pp. 286–94. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1014634. Accessed 11 June 2023.

[10] Carey, James W. “The Discovery of Objectivity.” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 87, no. 5, 1982, pp. 1182–88. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2778428. Accessed 6 June 2023.

[11] Schudson, M. (2011). Discovering the news: A social history of American newspapers. New York: Basic Books.