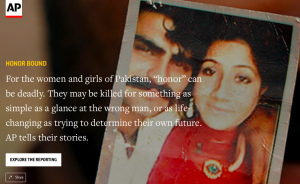

Honor Bound

In April 2014, AP Senior Correspondent Kathy Gannon was on assignment in Afghanistan with a colleague, photographer Anja Niedringhaus, when a gunman walked up and shot both women at close range. Anja died of her wounds, and Kathy spent the next year recovering from hers.

Gannon has covered Afghanistan and Pakistan since the 1980s. If extremists in the region thought they would scare her away, they were mistaken. She returned to her longtime base in Islamabad, Pakistan, at the start of 2016. Not only did she return, but she spent much of the year focused on a key issue involving religious extremism and cultural conservatism: the plight of women in the country. The result was a series called “Honor Bound,” detailing the horrific practice of “honor” killings and abuses in which women are treated as mere property by their families or society.

The injustice and cruelty can seem relentless. A young woman is burned alive by her mother for marrying without approval. Another is shot by her brother in a story that puts us inside the mind of a killer — and reveals the culture of peer pressure and misogyny that shaped him. Another woman finds no protection in fame: For flouting conservative norms on social media, she is murdered as well, a classic case of death foretold. Elsewhere, a young Hindu girl is abducted by a landlord, forced to convert to Islam and married off to an older man as “payment” for a debt. And in the final story of the series, a father trades a young daughter to a disabled older man in exchange for the groom’s sister, whom he wants for a second wife.

The series offered a multi-dimensional look at the phenomenon: how it reflects attitudes toward women; the hold that centuries-old traditions still have in the 21st century, such that women and girls risk being killed for a glance in the wrong direction, a demand to choose their own partner or a refusal of a marriage proposal. But it also told of the bravery of the women who defy tradition, challenge conservative culture, push back against those who would enslave them as bonded laborers. The series in its entirety can be found on the AP website.

how to tell this story?

At the heart of the series was a clash of value systems. One featured a fundamental belief that women are a commodity to be bartered, to be given to settle a debt or in exchange for a bride, or held up as the symbol of a man’s pride. Those beliefs conflicted sharply with the traditions and values of equality, human rights, women as independent beings, able to decide their future. Would we wage a war of value systems — to wage a clash of cultures? That didn’t seem quite right. We needed to tell the stories in a way that spoke for itself. We needed to delve beyond the surface horror of a practice, to find a way to tell a series of stories that would put the reader into this foreign society and mindset. Indeed, to make the reader understand how it can be that a father could marry his daughter to a far older mentally and physically challenged man.

We brainstormed, with Gannon maintaining a constant dialogue with local staff and editors at the regional hub in Cairo and in the United States. Most stories done by other news outlets had concentrated only on the girls, the women, the victims. Far more difficult, and in a way less appealing, was to explore the mind of those who could commit these crimes: the mind of a father who trades his teenage daughter for a second wife because his first could not give him a son.

Gannon decided to pursue this path, to seek to somehow understand a practice that appalled her and would have the same impact on most readers. Would the reader be outraged that the killer had the opportunity to explain, that his fears and anxieties were given a hearing? We knew we had to try, to help the reader understand how crushing poverty and centuries old traditions can enslave the perpetrator as much as the victim. In no way did this seek to excuse the crimes; but there is value, Gannon believed, in trying to understand.

impact

Gannon’s series told of crimes and injustices that had become so commonplace they managed to escape much notice even in Pakistan itself. She helped expose these outrages — but also took special care to put them into context. She explained that there were increasingly significant moderate forces in the country that were opposed to these practices and chronicled the work of two women to change the law. Late in the year, Pakistan finally tightened the law that had allowed families of the victims to “forgive” the killers, often family members as well, allowing them to escape punishment. One of the respected directors of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan said Gannon was making a difference with her reporting.

That type of fairness helps gain access, which can be difficult in a country where mistrust of outsiders runs deep. Gannon used her extensive network of contacts to discover and research cases and tease out details, in some case relying on activists or sympathetic officials. An example is the young police superintendent in Lahore who had in custody a brother who had killed his sister. The superintendent was so enraged by the murder that he ultimately agreed to grant access to the wholly unrepentant man before his transfer to a more-secured central jail.

As the year came to a close, Gannon said she is gratified to be back working “on stories I knew Anja would have loved. There were many times I saw images I knew I was seeing through her eyes.”