Why you should stop encouraging news consumers to blindly donate to Haiti relief

Last week I messaged a source of mine in Haiti near Port-au-Prince to ask how he’s weathering the storm that hurricane Matthew has wrought upon his country. He replied that houses in his neighborhood had fallen “victim to floods.” The good news? “No one has died.”

That’s more than people living on Haiti’s southern peninsula can say. The death toll—now officially at 336, though likely far higher—is a big part of why the world is paying attention to Haiti right now. It’s in the headlines, it’s in the ledes. It’s the reason news agencies continuously hunt for the highest figures: The higher your death toll, the more fresh, the more ominous your reporting appears, and the more likely it is that TV news stations, newspapers and news websites will choose your story over your competitor’s. (This weekend The New York Times wrote about the challenges of calculating a death tolls).

We should care that hundreds of people have died. But we shouldn’t only care when a storm hits. More than 9,000 Haitians have died from cholera in the six years since the United Nations introduced the disease there. Diarrhoeal diseases kill at least 4,600 Haitians each year. Those diseases are usually brought on by lack of clean water and sanitation — things with relatively simple and low-cost fixes that neither Haiti’s government nor the international aid community has invested in sufficiently to fix.

In fact, giving money to disaster relief in Haiti is probably one of the worst ways to spend your money. In most cases, by the time a disaster strikes, it’s simply too late to do very much. Billions of dollars flowed into Haiti following its 2010 earthquake, but the number of people pulled alive from the rubble by international medical teams likely measured only in the hundreds. When an earthquake hit Turkey in 1998, 98 percent of the people pulled from the rubble were saved by neighbors, relatives, friends — not internationals.

When disaster strikes, the first 24 or 48 hours are the critical windows in which to save lives. But even then, there’s precious little that emergency donations can accomplish. A friend of mine who works for a major aid organization in Haiti messaged me last week that “it’s awful trying to get to the south with the bridge down, blocked roads, etc. So sad.” She’s talking about a bridge on the same road I traveled back in 2010 to cover hurricane Thomas as it struck Haiti’s south. Indeed, bridges in Haiti fall frequently when storms hit. Without them, aid workers can’t get to the affected areas easily, or at all.

But how many of us have opened our wallets in the past five years to donate to the construction of bridges in Haiti — or roads?

More to the point, how many news outlets that are gaining clicks and ad revenue by reporting on the current death toll in Haiti bothered to report on any solutions to Haiti’s chronic infrastructure or health problems in the past? Absent any solutions-oriented coverage, the recent barrage of news about the tragic toll of Hurricane Matthew feels an awful lot like disaster porn.

In this December 2014 photo, a man navigates his boat toward an island off Haiti’s Southern peninsula — the area area hardest hit by Hurricane Matthew this month. (Photo by Jacob Kushner and used here with permission)

A better way

When disasters strike, news media tend to act as conduits for our money, writing on the assumption that news consumers can alleviate the crises through their pocketbooks. Our headlines, our leads, urge our audiences to focus not on the underlying causes of Haiti’s suffering, but on fleeting relief efforts:

“Aid Agencies Rush to Help Hurricane Matthew Victims in Haiti,” says Voice of America.

“Haiti Relief Efforts Step Up as Higher Death Toll Feared,” says the Wall Street Journal.

Corporations like Facebook, Apple, Amazon and T-Mobile make the Red Cross their default charity whenever disaster strikes, irrespective of that agency’s mixed record of helping Haiti in the past. Often, reporters naively follow their lead.

Having spent two years living and reporting in post-earthquake Haiti, following the money and reporting on failures in international aid, there are few charities that I feel comfortable recommending people donate to. I was saddened last week to see that even some of those were using this disaster as a means to fundraise.

There’s no denying that we tend to be more moved by emotional appeals and breaking news than by logic or reason. Perhaps there’s an argument to be made that now is the right time for media to spread the message. But that’s only true if we direct people to charities that do long-term capacity building work and have evidence that they do it well, rather than just the ones with the big names and the sad pictures.

I was encouraged to see that in its emails this week, the American Jewish World Service avoided the implication that donating money would immediately save lives from the storm. Instead, AJWS explained its long-term road map toward helping local Haitian organizations and institutions build the capacity to prevent such catastrophes in the future. AJWS wrote in an email that while “Most of the first-responder organizations will focus on food, shelter and clean water,” it would be focusing its efforts on “Rebuilding of infrastructure for partners who have reported damage” and preventing water-borne diseases from spreading in the coming days in communities that were the hardest hit.

“In an environment in which international aid is controversial, and is seen to only weaken Haiti’s efforts to establish autonomy and accountability, AJWS seeks to advocate for all aid organizations to work directly with Haitian national and local organizations – to give flexible support and to promote sustainable rebuilding and prevention work,” wrote the charity.

If an international charity can describe the complexity of Haiti’s situation — the long-term challenges and the long-term solutions — in a simple email, why can’t news outlets do it in their stories?

What you can do

On Friday a journalist friend of mine based in Kenya who has never been to Haiti was thinking about going there to cover the storm’s aftermath. There has to be a better way than chasing the storm.

The Solutions Journalism Network has an excellent toolkit for reporting news in a productive way — not by sending readers fumbling blindly for their wallets, but by identifying an initiative that took a deep look at a chronic problem, devised an evidence-based solution to it, and managed to put it into action.

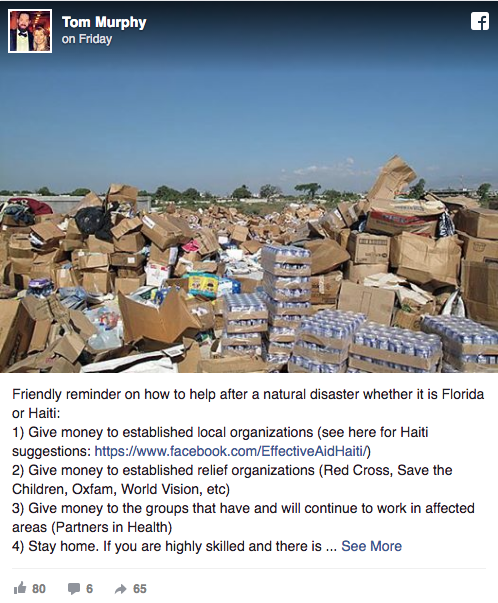

Yesterday, another journalist colleague of mine who has spent years writing about foreign aid came up with some basic guidelines to follow for giving to Haiti, most of which come down to the simple but essential rule of give cash, not stuff, and don’t fly down yourself.

But for journalists I would add another suggestion to the list: don’t encourage your audiences to give to relief in the first place. Direct them to science-based charity navigators like GiveWell, which analyzes the research behind different charities to identify where your money is most likely to do the most good. Your readers will soon learn that disaster relief is one of the most inefficient ways to save a life, but that there are other ways in which even a little bit of philanthropy can go a long way.

But for journalists I would add another suggestion to the list: don’t encourage your audiences to give to relief in the first place. Direct them to science-based charity navigators like GiveWell, which analyzes the research behind different charities to identify where your money is most likely to do the most good. Your readers will soon learn that disaster relief is one of the most inefficient ways to save a life, but that there are other ways in which even a little bit of philanthropy can go a long way.

Help your readers become effective altruists. An effective altruist would argue, correctly, that things like Hurricane Matthew ravishing Haiti are not truly “natural” disasters, but man-made ones. Florida has twice the population of Haiti, and yet the death toll there isn’t approaching 1,000 — it’s only 6. That’s the result of our investment in modern infrastructure and health systems, in taxpayer dollars being spent on welfare and other programs that help people meet their own needs.

We can prevent such travesties in Haiti too: Rather than encourage news consumers to throw enormous amounts of money to post-disaster rescue teams that are rarely able to save many lives once the storm has hit, let’s give them the tools to direct their philanthropy wisely toward preventing the next one.

Jacob Kushner, UW Journalism ’10, spent two years investigating foreign aid in Haiti.