Hours after the first presidential debate of 2016 concluded, Republican nominee Donald Trump took to Twitter to proclaim his victory. “Thank You! Four new #DebateNight Polls with the Movement winning. Together, we will make America Safe & Great Again! DonaldJTrump.com,” he tweeted. Underneath Mr. Trump’s message was a graphic displaying four polls from Breitbart, Variety, NJ.com and The Hill, that all conclusively showed Trump winning the debate.

Thank you! Four new #DebateNight polls with the MOVEMENT winning. Together, we will MAKE AMERICA SAFE & GREAT AGAIN!https://t.co/3KWOl2ibaW pic.twitter.com/Yl2XShopEv

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 27, 2016

But the polls Trump cited should not be taken as certain indicators of the debate results. Flash polls like the ones mentioned above, as well as online polls from other publications like MSNBC and Time magazine from after the first debate, are not at all scientific. As a result, while Trump and his surrogates propagate their message of victory using these polls as evidence, the polls provide no actual insight about who won or lost a particular debate.

One reason for not putting much value in the results of these polls is that most who respond to them are frequent visitors of the website where the poll is hosted. It is not surprising then, that on Brietbart.com, a conservative, pro-Trump news outlet, more than 160,000 people voted that they thought Mr. Trump won the first debate compared to 51,000 who believed the Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton won. In many cases, the results of these polls are merely reflective of the audiences that the websites attract and not potential American voters as a whole.

“They’re just garbage. They’re opt-in polls,” Professor Dhavan Shah, Maier-Bascom Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said. “In fact, many of them can be machined. You literally can set up systems that go and log in and vote hundreds of times, thousands of times. You can tilt the scales in one direction or the other. They do not represent any sample. Period.”

Users and advocates can easily affect the result of these polls. As Shah points out, computer programs can vote hundreds or thousands of times. These polls are more a reflection of fan support than anything else, as many message boards during the debate called for Trump supporters to flock to these various polls to support him. Sometimes just a simple refresh of an Internet browser allows debate watchers to vote for their candidate over and over again. A voter doesn’t even need to watch the debate to vote in such polls.

“Think of it like if you’re at Lambeau Field and the referees call holding on the Packers – 60,000 people at Lambeau Field say, ‘that’s not holding,’” Mike Wagner, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin’s School of Journalism and Mass Communication said. “That’s a huge number, 60,000 people, but of course they’re highly skewed toward liking the Packers. And that’s the same for someone who would go to [conservative website] Drudge to fill out a poll or [liberal leaning] MSNBC to fill out a poll. And so the difference is in scientifically valuable public opinion surveys everyone has an equal opportunity of getting contacted which is not the case when you’re talking about an Internet web poll.”

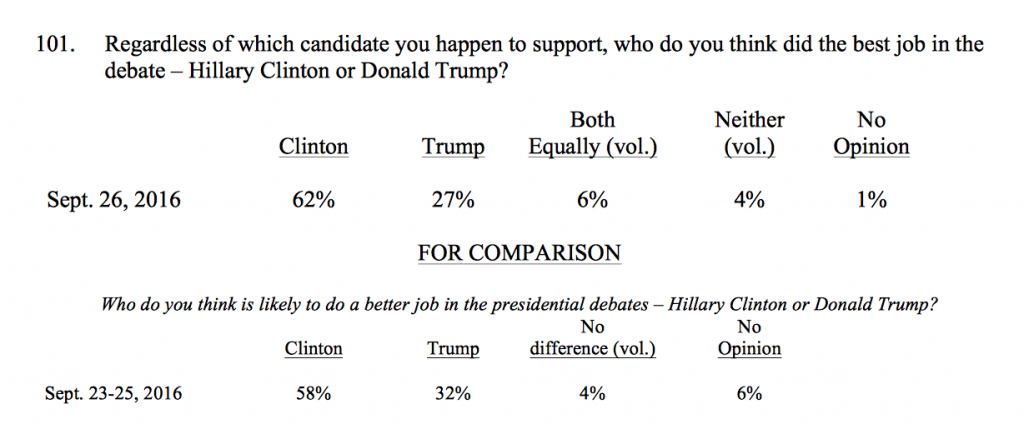

Post-debate scientific polls like the CNN/ORC poll or PPP poll are instead conducted using pre-screened debate watchers who planned on watching the debate and said they were willing to answer a poll immediately after the debate about their thoughts. And while these poll samples might slightly skew toward a particular party, their slight partisan imbalance doesn’t make the poll invalid because these polls are still representative of the United States’ voting profile as a whole.

CNN/ORC and PPP also do not conduct these polls as a means of attracting attention to their content, but instead to help inform the public. Flash polls, Wagner said, are designed to drive clicks and attract attention to the host website. They can be trying not so much to gauge opinion as to drive opinion.

“I wish they [online websites that conduct flash polls] would consider how running the results of a poll that is substantively meaningless harms their brand, but that doesn’t seem to be a concern for some of these places,” Wagner said. “I would actually make the argument that it isn’t ethical for journalistic outlets to report the results of unscientific polls.”

Debate polls look great - thank you!#MAGA #AmericaFirst pic.twitter.com/4peQ3Sswdz

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 10, 2016

Trump’s campaign frequently reports these polls to build support for his campaign, but it is hard to condemn him for doing so, according to Chris Wells, an associate professor in UW-Madison’s journalism school. Wells notes that many groups, political and otherwise, try to build support using unscientific online polls. But according to Wells, what journalists are doing or not doing to help people understand what these online polls actually represent raises ethical issues.

Many unscientific polls do get covered, but their flawed methodology is seldom mentioned. They are cherry-picked and used as equal evidence to counter a more scientific poll or focus group-based study. But because debate watchers can easily opt-in to game the system, voting countless times to support their own views, these polls have little actual merit.

“It’s as valuable as saying, ‘Well, I can look at out my window and see that it’s sunny here in Madison, and so therefore it is sunny in Seattle, Washington,’” Wagner said. “There is no bearing upon what you see in an Internet-based flash poll and reality.”

Trump repeated his claim that the polls had deemed him the winner after the second presidential debate. Politifact rated that assertion a “pants on fire” false claim.

Ben Pickman is a second-year student in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at UW-Madison. He is double-majoring in journalism with a reporting focus and history. His main journalistic interests include sports media and sports media ethics, sports and society, and political reporting.