It took a team of about 30 NPR reporters and editors to annotate live transcripts of the 2016 presidential debates, according to Amita Kelly, a reporter on NPR’s politics team.

It took a team of about 30 NPR reporters and editors to annotate live transcripts of the 2016 presidential debates, according to Amita Kelly, a reporter on NPR’s politics team.

The roster included journalists from politics, business and international security, with editors simultaneously working to clean up the transcript itself as well as the fact checks and analysis.

“We use the term fact check a little bit broadly,” Kelly explained. “Some were straight: is this true or false? But a lot of it is just the analysis that our reporters can provide, saying: ‘Actually, there’s more to the story.'”

NPR’s fact check featured an unfolding live transcript of the debate, with various claims underlined and linked to fact checks from NPR staff. The annotated transcript of the first debate drew more than 2 million views within 48 hours.

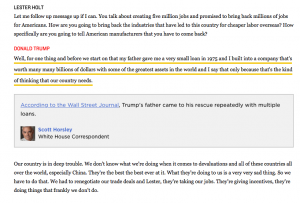

An example of a fact check from NPR during the first debate.

Because many of the claims the candidates made during the debate had already surfaced at some point in the campaign, the NPR team was able to rely on previous reporting to quickly verify information, according to NPR digital team member David Eads.

“The reporters are adding context and checking whether or not the statements are true, but there are also linking to stuff all around the media,” Eads said. “These became really great ways of catching up quickly on a lot of different issues. If we hadn’t had that kind of foundation of that reporting before, then I don’t think it would be quite as successful.”

But there are limits to this style of instant fact-checking, said Lucas Graves, a professor of journalism at the University of Wisconsin and author of “Deciding What’s True: The Rise of Political Fact-Checking in American Journalism.”

“Usually these claims are much more complicated to investigate than it seems at first,” Graves said. “If you were to try to decide from scratch whether some budget claim was true or false, and get that up in five minutes, you’re probably going to make a mistake.”

checking facts: a conversation

While the speed of the instant fact check may not always be possible, Graves said NPR’s fact-checking endeavor illustrates a conversational style that is trending in today’s journalism.

FiveThirtyEight live-blogged the first presidential debate.

Pointing to FiveThirtyEight’s election team, which takes a Slack conversation between reporters or experts on a designated topic, edits it for clarity and then posts it directly to the web, Eads said news consumers are looking for more of a dialogue than traditional journalism has offered.

“It seems that people want to hear a lot of voices, sort of in dialogue, and not this omniscient detached narrator that can provide journalism from the the 50s,” Eads said.

Kelly described the experience NPR created with the debate fact checks with contributions from reporters across beats as like watching the debate “with all of your smart NPR friends sitting next to you.”

“When Clinton, something comes up about her emails or a tax plan or a tax credit, I want someone to poke me and say ‘Hey! Actually, she’s been saying this all along, or this is different than what she said, or that’s actually not what those experts agree with,” Kelly said.

Eads noted that this particular style of journalism has the potential to fill in gaps left by social media.

“One thing that you have to be able to be successful these days, is provide a better experience than things like Twitter and Facebook,” Eads said. “And this managed to do that, in a way.”

the future of fact checking

Graves said he hopes the way this election cycle has shaped fact-checking continues.

Even in regular news pieces unrelated to the election, Graves said he’s starting to notice reporters make fact checks more freely. In the past, he said, journalists would refrain from challenging a source within a straight news report out of a fear of being accused of bias.

“There’s no good journalistic argument for repeating a claim in a news story that you know to be false without noting that it’s false,” Graves said. “I think journalistically, that’s indefensible, and we’re seeing a sort of cultural shift to accept that.”

As for NPR’s live fact check, he applauded the effort but hopes to see more fact-checking integrated into the debates themselves, either through moderators or video clips.

“If it’s built into the debate format itself,” Graves said. “The candidates themselves are actually confronted with the fact checks.”

Cadence Bambenek is a fellow for the Center for Journalism Ethics. She is a student in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.