Photo of AP Stylebook: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism

It started with a single word: Boy.

At a protest following the in-custody death of Freddie Gray, a black woman had been caught on video hitting and berating her teenage son for participating in the demonstration.

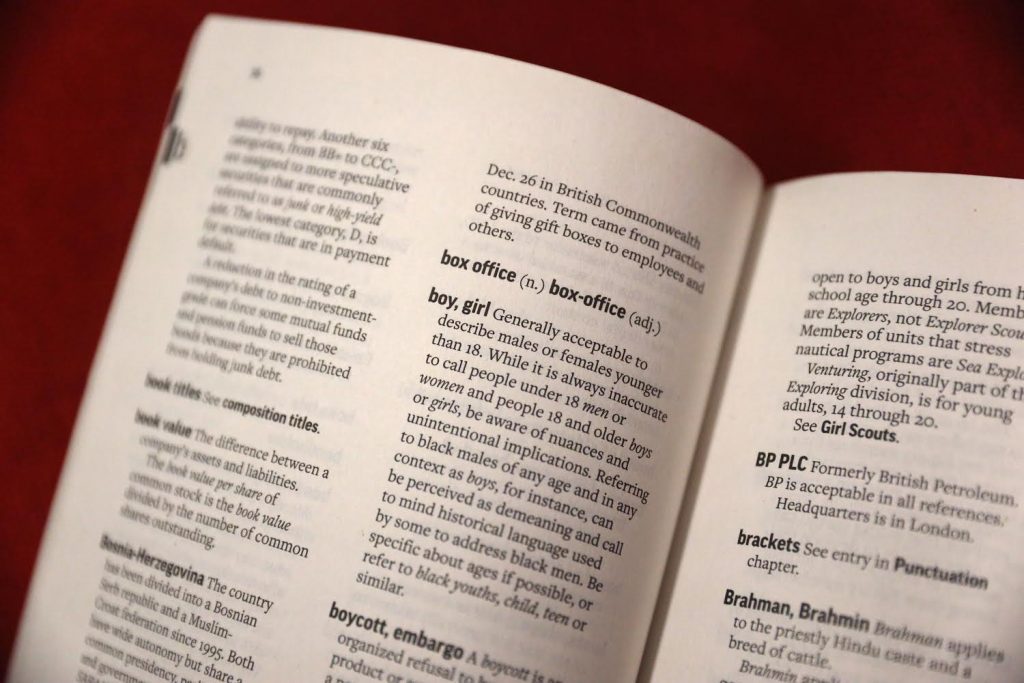

“I believe the headline was ‘Woman beats boy,’” Sarah Glover, president of the National Association of Black Journalists, recalled. “That really bothered me because the African-American male subject was not a boy. He clearly was a teen, if not a young adult, if not a man.”

But it wasn’t just the young man’s age that made boy the wrong word, Glover argued. The word itself, when used to describe black males, was historically derogatory.

“That really resonated with me as a clear example of everyday journalism which we can do better,” Glover said, “and I took it as a call to action to reach out.”

Glover asked The Associated Press if NABJ could submit suggestions for a revised AP Stylebook entry for boy. The Stylebook editors agreed, opening the door for the professional association to help shape the language used in American journalism.

NABJ proposed expanding the Stylebook entry to offer more context on what might have seemed like a simple term.

“Words do matter,” Glover said. “The Stylebook isn’t a dictionary… but it is providing context on how to use words.” The entry could not be complete, Glover argued, if it didn’t explain the term’s history with respect to black men. “The word has a different meaning when you’re talking about that population.”

“It no longer becomes a word around age. It becomes a word around power, from slavery to Jim Crow-era lynching, to violence and death that black men are subjected to,” Glover said.

Also pushing for the change was NABJ Vice President-Print Marlon A. Walker, who began his career as a copyeditor and calls himself “the grammar Nazi of our board.”

NABJ sent recommendations about several other terms as well, including multiracial, biracial, -American, and reverse discrimination, for Stylebook editors to consider. Several of those recommendations were adopted in the 2018 Stylebook.

An ever-evolving guide

This wasn’t the first time Stylebook editors had acted on recommendations from marginalized groups. In February 2013, Jen Christensen, then-president of the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association (now known as NLGJA/The Association of LGBTQ Journalists), wrote an open letter to then-Stylebook Editor David Minthorn requesting that AP revise the husband, wife, entry to allow those terms to be used to refer to people in same-sex marriages.

A week later, The Associated Press announced it would adopt the change beginning in the 2013 edition. In the same edition, the editors revised the illegal immigration entry, advising journalists, “Except in direct quotes essential to the story, use illegal only to refer to an action, not a person: illegal immigration, but not illegal immigrant.”

“The Stylebook team has been tackling more issues-oriented concerns in recent years,” Paula Froke, Stylebook lead editor, said in an email.

“We frequently seek feedback and advice from groups and people who are experts in certain areas or who have extensive background in topics we’re discussing,” Froke said. “It’s natural that we would turn to NAJA (Native American Journalists Association), NABJ and other journalism groups for their input on race-related topics and terminology.”

Making the preferences official

Of course, contributing to the Stylebook is not the only way in which communities shape the language journalists use. Organizations like NABJ, NLGJA and NAJA have long held their own style preferences and advised other journalists.

“We offer ourselves as a resource to The Associated Press and any newsroom that would want to tap the NABJ to get our insights on representation and communities of color,” Glover said. For at least 20 years, NABJ has maintained its own style guide, which explains many terms related to African-Americans and the African diaspora that don’t appear in the AP Stylebook.

NLGJA also maintains its own guide — available in English and Spanish.

Bryan Pollard, director of programs and strategic partnerships for NAJA, said for years Native American journalists found some Stylebook entries lacking.

“Well, I think any of us that are Native and have been in the journalism business, we all kind of have our own experience for looking through the AP Stylebook and finding an entry and being like, ‘What?’” Pollard said.

But NAJA had not formalized its style preferences until Froke contacted the organization for advice on creating an entry for Indigenous Peoples Day. NAJA’s board of directors took that opportunity to suggest changes to a few other entries as well.

“It wasn’t that the entries were wrong, necessarily, but we felt like they didn’t provide really clear guidance,” said Pollard. “But that kind of spurred the thought: If we have these style preferences, we can’t just sit back and rely on the AP to adopt these because they may or may not. That’s their choice.”

To make those preferences known, NAJA produced a one-page, die-cut insert, for sale on its website, that snaps directly into the Stylebook. “It’s literally our addendum to the AP Stylebook,” Pollard said.

In fact, so many groups now have their own guides that one veteran editor created a website to make them easier to find.

“I have been editing for over 20 years, and I’ve accumulated a lot of style guides written by communities telling people exactly how they want to be talked about,” said Karen Yin, founder of Conscious Style Guide. “I realized that this stuff is spread out all over the Internet, and wouldn’t it be awesome if somebody just put it all together on one website and linked to these fairly hidden resources?”

Usage requires awareness, Yin said. “If you don’t know it’s out there, you’re not going to be able to use it. So I see a lot of editors kind of just floundering. Most of us want to do the right thing, but we don’t know what it is.”

Going beyond the Stylebook

Yin initially focused on creating and compiling glossaries but soon realized that writers and editors would need deeper guidance to choose the right words.

“I want people to realize the importance of how content works with context,” Yin said. Because context and audiences vary, Yin said there are no one-size-fits-all terms. In one context, queer might be the right word; in another, it would be LGBTQ.

“I don’t know how your words are supported by the context, therefore I cannot say, ‘This is the word you should use.'”

While Yin’s website links to a wide variety of key glossaries, Yin has turned her own energy toward compiling and writing articles that help writers and editors — of journalism, fiction, or ad copy — to think deeply about their language choices.

“I’m trying to push critical thought more,” said Yin. “There are no simple answers. You need to just live conscious language.”

Yin aims to educate writers and editors about the “current mood and feeling” so that they can better anticipate the impact their words will have. That is, assuming they care: “If you don’t care about impact and you think intention is all that matters, then you’re probably not somebody who reads Conscious Style Guide.”

Pollard agrees that terminology alone is not enough. He said many journalists covering Indian Country don’t have enough context to tell stories accurately.

“Most mainstream journalists feel like they can just go in and cover it like they cover any other news story, and it’s really not true,” Pollard said.

Pollard argues that journalists covering Indian Country need to look at their stories through at least three lenses: news, culture and colonization. To help journalists understand those contexts, NAJA produced six one-page guides.

Say you’re reporting a story related to the Indian Child Welfare Act, for example. If you take 10 minutes to read NAJA’s guide to that law, you’ll be better prepared to tell that story, Pollard said.

“It will give you some really good background information on the law, some of the nuances of it, how it affects Native communities and Native people and Native children.”

Of course, there is only so much context one can learn from a single page, so NAJA gives newsroom trainings across the country on how to cover Indian Country more accurately and completely.

Some recommendations not yet accepted

Some changes suggested by advocates have not yet made it into the Stylebook.

Yin has been pushing since 2014 for Stylebook editors to add entries on bisexual and asexual. She would also like to see writers replace the opposite sex with a different sex or another sex in order to not reinforce that binary, and she would like writers to not use the phrase coming out every time a person publicly discloses their non-heterosexuality for the first time.

“It assumes that it’s something that we hide and then suddenly we are out of the closet now,” Yin said. “Not all people in the LGBTQ community have been in the closet, and we’d like to be able to talk about it without people thinking that we’re admitting something that’s shameful or secretive.”

Pollard, meanwhile, has been lobbying Stylebook editors to capitalize indigenous when referring to people or communities, as opposed to plants, for example. He said some outlets have already adopted that style.

“AP will eventually come around,” Pollard said. “They may be late to the game on that particular change, but I think that they’ll get there. But if I could snap my fingers and make a change right now, that would be the one.”

Meanwhile NABJ’s Walker is still trying to persuade Stylebook editors on one point.

“For me, black as a standalone noun should never be a thing,” Walker said, noting that white is never used as a noun except alongside black. The Associated Press still permits this use in headlines in order to save space, as in Chicago TV station WGN9’s recent headline, “How the Sears catalog revolutionized the way blacks shopped,” but Walker disagrees.

“At the end of the day, if you can find more space for other things, you should be able to find more space to describe who you’re speaking about,” Walker said.

Stylebook editors work on updates and additions throughout the year, considering ideas from a variety of sources. Among those sources are public suggestions submitted at the online suggestions link, questions from Twitter and Facebook, emails, recommendations from other members of the AP staff, and the observations of Stylebook editors themselves. (You too can make a Stylebook suggestion by emailing Froke at pfroke@ap.org.)

“The Stylebook team reviews suggestions and decides which ones most merit attention,” Froke said. “We then discuss ideas and approaches, craft an initial entry, continue to discuss, and revise as warranted. A great deal of time and thought goes into every entry.”

Revising the “Bible”

Revising the Stylebook is just one step in changing the narrative about people of color, said NABJ’s Glover. In June, NABJ will continue its annual Black Male Media Project for the third year, and this time they’re considering issuing guidelines for visual journalism. Glover, who trained as a photographer, said the group seeks, among other changes, to counter the practice of using mugshots to depict individuals who are not suspects in the story.

“If they’re a victim, they’re a victim,” Glover said.

Changing the Stylebook might be a single piece in the puzzle, but Glover calls it “a huge industry impact.”

“Those [AP] datelines show up all over the world, so this certainly has the capacity to have a major impact worldwide in terms of how black males are covered in general,” Glover said, adding that as journalists consult the Stylebook, the revisions will prompt newsroom conversations about context and impacts on communities of color. “Editors and reporters will have discussion around covering diverse people and communities and not just reach for the low-hanging fruit.”

Walker agrees. “It’s exciting,” he said of the opportunity for journalists of color to help shape that conversation. “As a journalist, the AP Stylebook is the Bible. So to be able to say that I contributed to changes in the Bible is an amazing thing.”