On July 20th Costa Rica woke to tragic news. María Luisa Cedeño, a 43-year-old Costa Rican anesthesiologist and head of the Anesthesiology and Recovery Service at the private Hospital Cima, had been murdered at the five-star hotel La Mansión Inn in Manuel Antonio, Quepos. She was found in her room after a weekend of relaxation at one of Costa Rica’s most renowned beach towns.

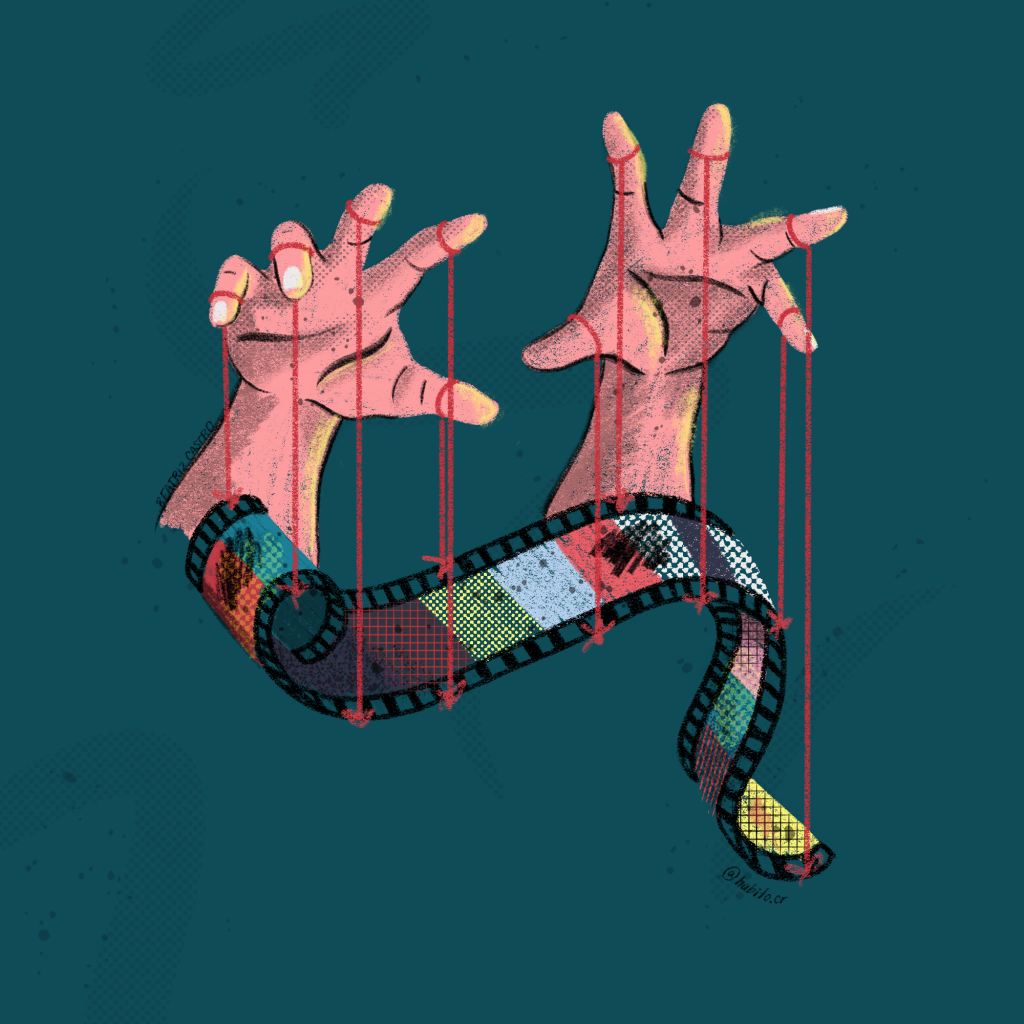

Cedeño’s death sparked intense journalistic coverage. But the Costa Rican media organization Teletica, one of the mainstream television channels in the country, stood out for its striking and unethical coverage of Cedeño’s death.

Its weekly show 7 Días (7 Days), which is dedicated to interpretative journalism, aired a special episode on August 31st called “El crimen de la habitación número 3” (The crime of room number 3). The story quickly prompted criticism from national institutions in Costa Rica and outrage on social media, with critics accusing the story of imbalance and questioning the use of a reenactment for a case still under investigation by the Costa Rican authorities.

The National Institute for Women (INAMU), the College of Medicals and the College of Journalists spoke out publicly against 7 Días. The show’s director, Rodolfo González, who is a journalist and lawyer, proceeded to apologize publicly on September 2nd on behalf of the media and Barbara Marín, the journalist responsible for carrying out the news story. Teletica then removed the story from its website.

While reenactments are more often used in documentaries, their use in journalism is an ethically delicate matter. The Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics says re-enactments should be “clearly labeled.” The journalistic guidelines of PBS’ long-form news documentary Frontline also cautions that reenactments “must be clearly and unmistakably labeled” and that “public affairs programs in particular need to use these devices with great care.”

The 7 Días program seems to have lacked that care. According to Larissa Arroyo, a Costa Rican lawyer specializing in human rights and director of the citizen association ACCEDER, the reenactment, which presented the victim as cutting loose and drinking alcohol, did not inform so much as serve as a moral “lesson” to María Luisa Cedeño, her family and women in general, one that pretends to show that certain behaviors run the risk of getting any woman killed.

“They start assuming and acting out ridiculous images [or videos] of situations that we do not really know about. That is very painful for everyone. If you are not careful about that on television, it can become an absurd narrative of the good and the bad, of love and hate. It becomes a soap opera.”

Alejandro Fernández

“It becomes an emblematic case. She [was] a successful woman, a professional woman, a socially and culturally fulfilled woman,” Arroyo said. “And in spite of that, this ends up happening to her.”

But the reenactment also contained another lesson – this one for journalism itself.

“In the case of journalism,” Arroyo said, “it’s very important to know how to approach it and not have examples like these ones because the task of informing and reporting is not being fulfilled.”

For Alejandro Fernández, a senior data journalist at PlayStation, the 7 Días’s story presented a series of assumptions and images acted out without any meaningful context.

“They start assuming and acting out ridiculous images [or videos] of situations that we do not really know about,” Fernández said. “That is very painful for everyone. If you are not careful about that on television, it can become an absurd narrative of the good and the bad, of love and hate. It becomes a soap opera.”

Reenactments as symbolic representations

The use of a reenactments as a creative tool in telling crime stories is a “slippery slope” because it can act as a stressor for the audience, the victim and the victim’s relatives. For Sarah Shourd, a US trauma-informed journalist and former John S. Knight fellow at Stanford University, reenactments deserve critical attention.

“I think we have to be more careful of the audience being deceived by our use of creative tools, creative reenactments being one of those tools,” Shourd said.

For her, journalism has the responsibility of taking into account the impact of stories on people’s lives as well as understanding reenactments as symbolic representations of a story.

“It’s completely unethical to create a representation of a crime as the truth when that crime is still being investigated and still undergoing in its process in the legal and court system.”

Sarah Shourd

“Reenactment has the word acting. It’s using the human form to create the illusion of an event,” Shourd said. “That is dangerous territory when you’re using an actual human body to symbolically represent another human being’s life.”

The dangerous territory in Cedeño’s case was enhanced by the fact that her case is still under investigation. For Shourd, reenactments are an inherently unethical tool while a legal case is underway because it interferes with the process.

“It’s completely unethical to create a representation of a crime as the truth when that crime is still being investigated and still undergoing in its process in the legal and court system,” Shourd said.

The unethical aspect of reenactments is not limited to questions of representation. There are also serious psychological components. How do reenactments affect the audience, the victim and the victim’s family?

The psychological impact of reenactments

According to Dr. Debra Lee Kaysen, a US clinical psychologist and professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Stanford University Medical Center, when carrying out a story about a sensitive topic such as violence against women, the sources should be given control over their narrative. Otherwise journalism risks exposing victims in a public space.

“It is really [about] helping someone understand what is going to happen with their story,” Kaysen said. “And what might happen with it in a public space and what the person’s cons and risks [are].”

The same rule applies to interviewing the relatives of the victim.

The impact reenactments have on audiences is another critical ethical consideration. In cases of violence against women, dramatizations can reinforce myths about sexual violence against women, including that the violence was the woman’s fault because of how she was dressed or that it is the victim’s responsibility to not be assaulted.

“Often those are done in such a dramatic way that it can reinforce some of those beliefs,” Kaysen said. “And it makes it seem more like a movie, something that you passively experience versus really hearing a story in someone’s own words.”

Dr. Elana Newman, a US clinical psychologist, research director at Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism and psychology professor at the University of Tulsa, said that sensationalized violence can also serve as a trigger for people who are suffering from grief and can be distressing, demoralizing and insensitive. To avoid sensationalism and damaging narrative framing, Newman points to the general journalistic coverage recommendations of the Dart Center.

These include: being respectful, taking your time, being honest about what information you need, being very clear about your informed consent, allowing survivors to take the lead, suggesting they bring support with them, not rushing and not asking for inessential details.

“I often ask journalists to write and then go back through it and think: if that was my family member or someone I loved, is there anything I would change in tone?,” Newman said.

“I often ask journalists to write and then go back through it and think: if that was my family member or someone I loved, is there anything I would change in tone?”

Dr. Elana Newman

According to Mary Rogus, a US associate professor of journalism at the E.W. Scripps School of Journalism at Ohio University and former television reporter, producer and executive producer, reenactments should never be used because of the re-victimization it entails.

“Ethically, I don’t think they should ever be used because of the potential of re-victimizing the victims and family members of the crime,” Rogus said. “It violates the very basic ethical principle of not deceiving the audience.”

“You can do all kinds of damage to those who were trying to get over the loss or the injury or the harm to a loved one,” Rogus said.

The journalistic implications of reenactments

Rogus teaches her students how to report these kinds of stories in a respectful manner by asking an essential question.

“How would you report the story if sex was not part of it?,” Rogus said. “Treat it the same. Don’t treat it any differently. That’s how we get rid of some of the stigma and that’s the way victims will feel more comfortable coming forward.”

Like Rogus, Dr. Chris Allen, a US journalism professor at the University of Nebraska Omaha and former television news producer and television assignment editor, reenactments are never a good choice in television news stories because they are not portraying the truth.

“Journalism is storytelling based on facts and you cannot do a recreation without taking license with the facts. And that’s never good,” Allen said. “The victim in the video is not the victim. The perpetrators in the video are not the perpetrators. The crime is not the crime. It is never an accurate recreation of what we think happened.”

For Allen, reenactments are an unethical way to tell a story.

“When we put somebody else into the living role of the victim, it’s almost like a tear in the fabric of ethical reality,” Allen said.

He also believes that this adds into creating a false narrative about women.

“Every time we blame the woman or make the woman helpless, we damage the reality for women: for girls growing up watching this, for teenagers, for young adult women and for elderly women all along,” Allen said.

“Journalism is storytelling based on facts and you cannot do a recreation without taking license with the facts. And that’s never good. The victim in the video is not the victim. The perpetrators in the video are not the perpetrators. The crime is not the crime. It is never an accurate recreation of what we think happened.”

Dr. Chris Allen

“We create a false narrative about women and in that way, empower those men in our society who are predisposed to violence. We empower to continue to create the violence against women,” Allen said.

For Dr. Donna Halper, a journalism Associate Professor at Lesley University, former deejay, music director, radio consultant and the woman credited for discovering the classic rock band Rush, reporters that are addressing sensitive topics must actively question their own journalistic process.

“It’s much easier to tell the story through the tropes, narratives and stereotypes of your culture until somebody calls them into question,” Halper said.

To question the process means to be fair to the facts.

“When I train journalists, I teach them two things: be fair to the facts and don’t get out in front of the facts,” Halper said. “If you don’t have the information, don’t just make it up. Don’t speculate. Don’t guess. Don’t put two things together that may not have been put together. You’re not a legal expert, you’re a reporter.”

Being fair to the facts implies looking for all the sides of story to have a balance, fairness and providing context in an ethical manner.

Context was not present in the story aired that 7 Días aired in Costa Rica. For the Costa Rican journalist Fernández, that lack of context led to the story having the wrong focus.

“The social approach and framing that we do about these events as a society is distorted. It does not reflect what is going on. We do not focus on what’s important,” Fernández said. “They forget that a woman was murdered. It begins to turn into an absurd narrative. A human being was killed and it is happening with much more frequency.”

For Fernández the story raises a very basic and essential question, “what do we learn from this as a society? Which is the moral?”

[CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article referred to Debra Kaysen as a “psychiatrist.” Kaysen is a clinical psychologist and professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Stanford University Medical Center. We regret the error.]

The Center for Journalism Ethics reached out twice to the Costa Rican director and journalist Rodolfo González. The messages sent were seen and unanswered. The Costa Rican reporter Bárbara Marín was also contacted. She did answer and was open to an interview, but never gave it because she had to have the approval of the director Rodolfo González. María Luisa Cedeño’s case is still under investigation by the Costa Rican authorities.

The Center for Journalism Ethics encourages the highest standards in journalism ethics worldwide. We foster vigorous debate about ethical practices in journalism and provide a resource for producers, consumers and students of journalism. Sign up for our quarterly newsletter here.