Photo by Koshu Kunii on Unsplash

Doug McLeod, Evjue Centennial Professor in the School of Journalism & Mass Communication at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, first conducted research on protest narratives nearly 40 years ago, when he began analyzing how the media helped shaped public opinion about anarchist protesters in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, in the mid-to-late 1980s. During this time of nationwide Black Lives Matter protests, his research provides a powerful way of framing or re-framing the stories we tell about protests. Here Professor McLeod has compiled his five recommendations for ethical protest coverage.

1. Elite framing

Problem:

Too often, social protest is covered from the perspective of elite power holders. This is in part the result of the people news media typically use as sources for articles about protests: politicians, law enforcement personnel and other institutional sources (e.g., business leaders, interest group representatives and academics). This often presents a very top-down view of the world that works to reinforce the interests of the existing power structure.

Recommendation:

Talk to the protesters and not just in the heat of protest when passions are running high. Take their perspectives seriously. Give them a legitimate voice in the social discussion and not just while the protest is going on.

2. Episodic vs. thematic framing

Problem:

As a result of journalistic conventions and the desire to demonstrate objectivity, most news stories about social protest are framed episodically rather than thematically. That is, it’s easier to maintain objectivity when you describe the events that occurred than it is to delve into the underlying issues and explanations of why things are occurring the way they are. This is especially true for hard news stories (as opposed to opinion pieces and news analysis).

In protest situations, particularly in television news, this means showing what is happening when it is happening and focusing on the actions of the protest rather than addressing the underlying issues under debate or the reasons for the protest. It requires more time and effort to cover things thematically rather than to report on events as they are happening.

Recommendation:

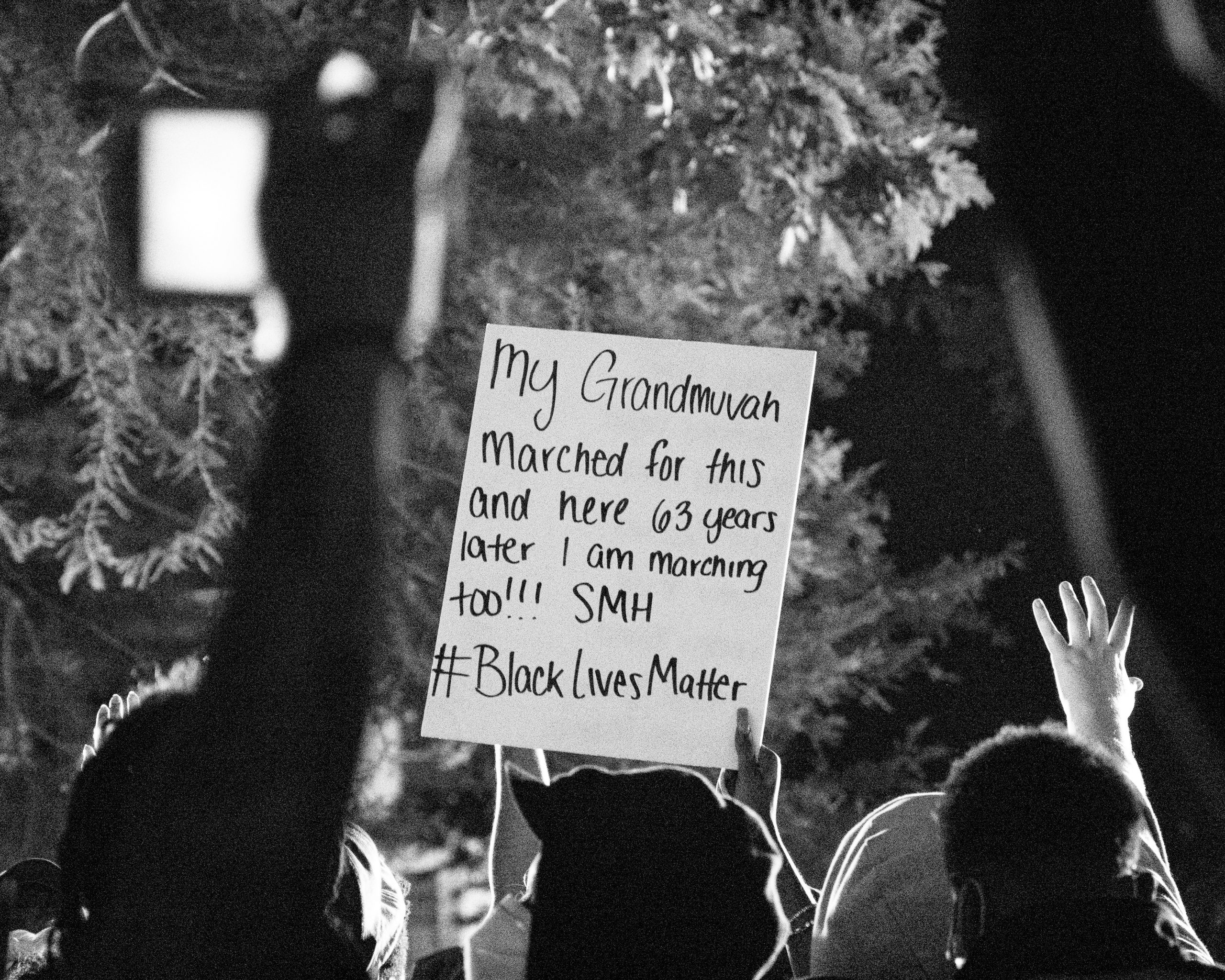

Balance the episodic coverage with analyses of the underlying issues. Take historical context into account, both in terms of the immediate context for the protest and the long-term historical context. It’s impossible to understand what is happening today without addressing short- and long-term historical contexts (e.g., racial oppression, structural inequality, etc.).

3. Protesters vs. police framing

Problem:

Protests are often covered as a contest between the protesters and police. The story is often structured around protestors engaging in destructive actions and the police responding — i.e., protesters engage in an action (e.g., civil disobedience) that requires the police to restore order and protect the public. This creates an “in-group/out-group” situation in which the protesters are portrayed as a deviant out-group, while the rest of us are the in-group. This builds public hostility toward protesters as an out-group threat, with the protesters being seen as deviants, rather than as active participants seeking social change.

Recommendation:

Remember that protesters are part of the community and that they are citizens actively engaged in trying to bring about positive social change. Whether the audience agrees with them or not, it is important to see them not as troublemakers but as active citizens who are expressing opinions and attempting to make changes in society.

4. Characterizing the protest movement based on small, inappropriate samples of individual protesters

Problem:

News media often gravitate toward the most vivid and dramatic individuals and actions of the protest. When they show protesters, they tend to show those who are engaging in actions like smashing windows, lighting fires and looting, all of which makes for good visuals for news stories. TV coverage in particular often shows long shots of burning cars and buildings, tear gas, rock throwing and other violence. Often times, these actions are being carried out by a small fraction of the protesters, or in many cases by people who aren’t even part of the protest movement at all (outside agitators or opportunists who have nothing to do with the movement but want to take advantage of the opportunity to engage in violence, damage property or steal).

When the audience sees these images, they will often make generalizations about the protesters (and potentially even question the legitimacy of protest as a form of democratic expression) that are based on a small and non-generalizable sample of the larger protest movement. That is, the audience assumes that all protesters are engaging in the featured actions, when that is not the case for a majority of protesters. We’ve seen examples where this kind of attention to a small subset of people can derail a movement. The larger concern is that, over time, it also breeds social contempt for protest and a lack of recognition of its positive benefits.

Recommendation:

First, operate with the assumption that protest is healthy for democracy and that engaging in protest is a form of democratic expression and a sign of a healthy democracy. Second, pay attention to non-violent protesters, characterize the movement fairly and recognize protesters who are not engaging in violence by paying attention to them and their motives and actions. Third, recognize when actions are being conducted by those who are not part of the movement (as seems to be common in the current protest).

5. Lack of empathy for the disenfranchised before, during and after protests

Problem:

Burning a police car may not seem understandable when viewed outside of a larger context. Violence results from the frustration that stems from the feeling of being ignored. It comes from persistent problems like racism, inequality and unfair treatment. People get frustrated when they are not given a voice, when problems persist and when the system ignores or oppresses whole classes of people. This drives people to protest to try to get attention and to initiate change.

Recommendation:

If voices only get attention when violent protest occurs, then you are probably going to get more violence. As societal watch dogs, journalists should take an interest in social problems on a consistent basis, not just when violent protest flairs up. They should seek to give attention to voices and concerns from all sectors of society, rather than just taking the easy route of practicing transmission belt journalism that attends to the agenda of elite power holders.

Journalists should think about giving voices to all sectors of society under normal conditions (more than just in the context of the news peg of a protest). But when protest does occur, journalists should pay special attention to the voices of the protesters, giving them the opportunity to frame their grievances in their own words. Moreover, journalists should recognize not only that these voices exist, but that they are often a source of positive social change.

For example, with the advantage of 20/20 hindsight, most Americans, including journalists, would recognize the tremendous contributions of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and ‘60s in bringing about positive social change in the United States. And yet we often fail to recognize the value of such actions when they are occurring in real time.

For more on McLeod’s work and on media framing of protest, read this recent article from The Atlantic, see this video from Vox, or read this article by Indiana University Assistant Professor of Journalism Danielle Kilgo.

The Center for Journalism Ethics encourages the highest standards in journalism ethics worldwide. We foster vigorous debate about ethical practices in journalism and provide a resource for producers, consumers and students of journalism. Sign up for our quarterly newsletter here.