I never thought I would write this: I was troubled by something, and Donald Trump helped me figure it out.

Coming off the recent confrontation between protesters and journalists at the University of Missouri, I felt unsettled. My social media feeds — loaded with journalists, educators and students — almost immediately dissolved into a binary. Many in my circles decried attempts to deprive reporters of their rights to be doing their jobs in a public space. You were either for the free press rights of journalists or you were against. I couldn’t even raise questions about the protesters’ perspectives in comments without being derided for not giving the First Amendment a full-throated defense.

So here it is: of course journalists have a right to report in public spaces if people don’t have a reasonable expectation of privacy. The prof was wrong, and yes, it was particularly regrettable on a campus housing one of the world’s most noted journalism schools.

But as I told my students in discussions of the controversy, if we’re going to move forward on race, we need to do better than a binary. We need to take a serious look at the protesters’ lack of trust in news reporters and concerns about having their narratives misconstrued by media that all too often get race wrong. And we ought to think about how locking media out of movements has power to perpetuate and expand the wrongs we’re already not righting.

Yet I was still troubled.

Enter: The Donald.

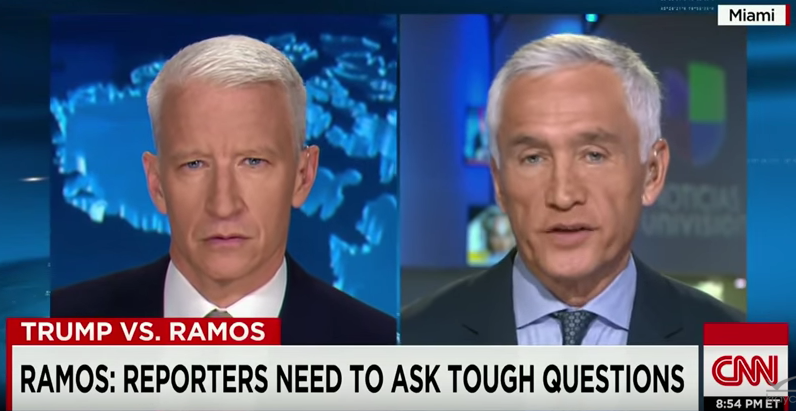

When the GOP candidate recently said of a black protester at one of his campaign events “maybe he should have been roughed up,” it called to my mind Trump’s security earlier removing Univision reporter Jorge Ramos from a press conference. My concern then crystallized for me. News media and citizen protesters both deeply need their rights to free expression and assembly when taking on powerful forces like Trump, who have tapped into racial discord for political advantage. Yet Mizzou demonstrated that many do not see the union in that struggle. Both sides seemed irreparably wedded — to quote Nat Hentoff — to “free speech for me, but not for thee.”

The struggle is shared

The thin understanding of the First Amendment among media friends and colleagues in the wake of Mizzou stunned me. First and foremost, they equated freedom of “the press” with freedom of “established news media.” But a look at free expression case law in the 20th Century (there’s almost none before that) shows a U.S. Supreme Court skeptical of that reading. The amendment’s ban on “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press” refers not to press as institution, but as instrument, scholars argue. It does not cover individual speakers via “speech” and news media via “the press.” It covers spoken and written expression.

It’s critical to remember that the Bill of Rights, including the speech and press clauses of the First Amendment, are individual rights, not institutional ones. And the fight for those rights has been long, convoluted and often tightly tied to social upheavals of the time. It should be lost on no one that one of the nation’s most important cases upholding freedom of the press was actually a civil rights case.

In 1964, the Supreme Court held in New York Times v. Sullivan that public officials had to prove what is known as “actual malice” when bringing libel suits related to their official conduct. The particulars of that standard are not important here. What’s key is that the decision made it far more difficult for public officials to win libel cases.

How is this related to civil rights and the struggle for racial equality? In the case, Sullivan and others had sued the Times over an ad titled “Heed Their Rising Voices,” which sought to raise funds to help defend Martin Luther King Jr. Libel litigation had been an incredibly effective weapon for Southern officials trying to intimidate journalists, and the national media in particular, from reporting on the civil rights movement. At the time the Sullivan case was decided, news media faced hundreds of millions of dollars in libel judgments in cases brought by politicians and authorities to silence coverage critical of their behavior.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Sullivan overturned these outstanding judgments, finding that public officials can successfully sue for false statements that damage their reputation only when they can show the publisher knew those statements were false or had reckless disregard for the truth. This standard is tremendously protective and liberated national media in reporting on civil rights and racial prejudice in the South.

Learning lessons

This history lesson is important for both journalists — including all the pals in my social media feeds — and protesters to bear in mind. Let’s start with those student protesters on the quad at Mizzou. I understand the lack of trust. Decades (centuries, actually) of flawed and biased reporting, intractable stereotyping and newsrooms that are anything but racially and socioeconomically diverse. These are the things that rightfully prompt these students of color to see established news media as yet another institution that furthers white power and squelches progress on race.

King and his fellow civil rights leaders might have felt the same way. After all, where was the New York Times during what Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative justifiably called the “racial terrorism of lynching” throughout the South after the collapse of reconstruction? Where were local newspapers fighting back against poll taxes, literacy tests and other attempts to deny voter rights? The answer: Nowhere to be found.

Yet no matter how flawed or how late these news media were, civil rights leaders recognized them as an essential tool in the struggle. It made strategic sense to stay open and connected, regardless of prior and current poor treatment. And indeed, I cannot imagine the historic resignation of top University of Missouri administrators without the pressure brought by international media coverage of the protests and statements by the school’s football team.

An alum recently asked me how in the world student protesters at Yale and Princeton could reject the Bill of Rights as inventions by white men to preserve their own power. I answered, “Two words: Jim Crow.” In the U.S., we have never come to terms with the legacies of legalized segregation and the lasting effects of suppressing the rights of some citizens based on their race. The protesters’ viewpoints are easily apparent to me even though, as a white woman, I have never lived their reality. Yet it was national media coverage of their protests that informed me last week that President Woodrow Wilson was responsible for a disastrous resegregation of federal employees. I’d certainly never learned that before.

In the main, preserving access for news media will further these students’ causes, even when coverage overall can rightfully be attacked.

Rights and responsibilities

But most of the media-focused commenters in my feeds would have it stop there. It is up to the protestors to understand that we have a right to be there and it’s ultimately in their own interests. It’s up to citizens to appreciate the protections of the First Amendment and see how vital a free press is to democracy.

I couldn’t disagree more. Those of us involved with news media — whether as journalists, students or educators — have a duty, an ethical obligation, to build trust with our communities and help ensure that understanding and appreciation.

The philosopher Isaiah Berlin (who I now know is also a favorite of Nicholas Kristof’s) poses an interesting pairing of our freedoms — one that I’ve always found especially applicable to news media. The first concept is the one we all think about when we consider liberty, what he calls “negative freedoms.” This liberty depends on freedom from interference by others. In journalism, this means government is restrained from meddling in our activities – the press is “free from” interference.

But we often ignore Berlin’s twin concept, a positive or affirmative view of liberty. This tells us that people also have freedom to make decisions and serve as their own masters. The press is “free to” serve the public’s interest and build trust. It’s this second obligation that seems to get lost in cases like Mizzou. We’re so busy defending our “freedom from” that we forget to maximize our “freedom to.”

This kind of moral certainty, the absolute defense of a value we hold, troubled Berlin, who wrote, “Indeed, the very desire for guarantees that our values are eternal and secure in some objective heaven is perhaps only a craving of certainties of childhood or the absolute values of our primitive past.”

And I think, in the end, it’s what troubled me. In so staunchly defending our rights, many of us overlooked the question of our responsibilities. In demanding to know why we were kept out, we failed to ask why people didn’t trust us enough to let us in. And that, to me, is the most important lesson Mizzou can teach us.

This piece originally appeared on MediaShift. Reposted here with permission.