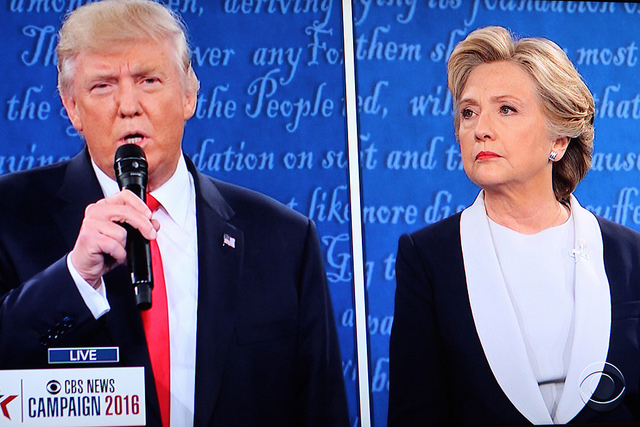

In the turmoil of a Trump election victory, and the dawn of a robust right-wing American government, it is time to do journalism ethics with utmost seriousness.

Journalism ethics is not a set of formal rules that students are forced to memorize and then find these ideals inoperable in the workplace.

Journalism ethics is the heart and soul of why you are a journalist, and why it matters.

Today, this soul-searching begins with a large question: What sort of journalism does America need to meet the great political challenges ahead?

What is the point of journalism practice in a time of Trump?

My answer is: to protect liberal democracy by embracing three related duties:

- the duty to advance dialogue across racial, ethnic, and economic divisions

- the duty to explain and defend pluralistic democracy against its foes

- the duty to practice the method of “pragmatic objectivity”

The duties work together to promote an egalitarian, plural, tolerant, democratic polity, which should be the political goal of public journalism. The duties work against a populist democracy dominated by a “strong man,” where freedom is freedom for the most powerful and abrasive.

The duties oppose the untrammeled, vengeful will of intolerant citizens who see the election as a “winner take all” victory for their side.

trump time

One cannot discuss the point of a practice in the abstract. Journalism ethics begins with some perception of the media’s social context. What is this context?

We live in a time of danger for moderate, liberal democracy with its divisions of power, freedom of expression, protections for the rights of all citizens, and the empowerment of minorities despite the displeasure of traditionalists.

Trump time has been a long time coming.

It has been long prepared for by: bad education, American insularity, and the myth of exceptionalism; incorporation of fundamentalist religion into politics; the deepening of economic inequality; seeing strength in guns and the person of violence; mistaking ‘in-your-face’ ranting for honest, democratic communication; and the worship of fierce partisanship over compromise.

Other contributors: An extreme patriotism which views those who disagree as enemies of the state; regarding America as white, male-dominated, and Christian; an insouciance toward fact and a suspicion of intellect; the preference for character assignation over rational argument; a fear of ‘others’ and the replacement of thought by slogan.

The result? A society populated by too many politically ignorant and apathetic consumer citizens, easy targets of demagogues. Now, these unsteady forces have the power of social media to create a totalitarian mindset in the heart of what was once the world’s greatest liberal democracy.

What to do?

Given this uncertain future, what should journalists do?

There are two options that should not be followed. One option is for journalists to counter the bombast and distorted statements of the Trumpites by producing a bombastic, counter-balancing opposition press. There is already too much rant-induced media.

“Here is where the first media duty arises: the duty to promote dialogue across divisions.”

The second option is for journalists to see themselves, delusionally, as only neutral chroniclers, as stenographers of ‘fact’ as the political drama unfolds. This is an outdated notion of objectivity formulated in the early 1900s for a different social context.

The best response lies between journalistic ranting and the mincing neutrality of stenographic journalism: it is a democratically engaged journalism committed to three duties.

A democratically engaged journalism is not neutral about its ultimate goals. It regards its ethical norms and methods as means to the flourishing of a self-governing citizenry. Here is where the first media duty arises: the duty to promote dialogue across divisions.

In a column on this site over a year ago, in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attack, I talked about the media’s duty to mend. Journalists have a duty to convene public fora and provide channels of information that allow for frank but respectful dialogue across divisions. They seek to mend the tears in the fabric of the body politic.

In a time of Trump, the duty to practice dialogic journalism is urgent. This means challenging stereotypes and the penchant to demonize. It means linking the victims of hate speech to citizens appalled by such discrimination, building coalitions of cross-cultural support.

Go ‘deep’ politically

However, fostering the right sort of democracy-building conversations is not enough.

Conversations need to be well-informed. Here is where the second duty arises.

Journalism needs to devote major resources to an explanatory journalism that delves deeply into the country’s fundamental political values and institutions, while challenging the myths and fears surrounding issues such as immigration.

The movement of fact-checking web sites is a good idea but insufficient. It is not enough to know that a politician made an inaccurate statement. Many citizens need a re-education in liberal democracy—those broad structures in which specific facts and values takes their place. They will be called on soon to judge many issues that depend on that civic knowledge.

“Journalism needs to devote major resources to an explanatory journalism that delves deeply into the country’s fundamental political values and institutions…”

John Stuart Mill once said that if we do not constantly question why we hold basic beliefs, they become “dead dogma.” How many citizens would be hard-pressed to say what democracy is (beyond voting) or exhibit an understanding of the history and nature of their own constitution beyond phrases such as “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”? How many have a virulent and imbalanced commitment to the Second Amendment alone?

Such a democracy is flying blind and vulnerable to demagogues.

Here is a small list of some topics for explanatory political journalism:

- The idea of a constitutional liberal democracy: Not liberal in the derogatory sense of favoring big government but liberal in making the basis of society the protection of a core of basic liberties. Plus, the idea of constitutional protection of the rights of all citizens, including minorities, against the wavering, often tyrannical, will of the majority.

- The division of powers: The extent of the powers of a president and his duty to uphold constitutional rights including not threatening action against critical speakers. Also, the idea of judicial independence from any president who would try to tell the courts what rights to recognize or reject.

- Deep background on immigration: Especially the difference between immigrants and refugees, the international refugee agreements, and the human face of the immigrants and refugees who come to this land.

- The meaning of political correctness: Its origins, the abuse of the term, and its ‘cover’ for hate speech. Plus investigations into groups that support hate speech and thinly ‘disguised’ racism online.

- The difference between a free press and a democratic press: A free press values the freedom to say what it likes, no matter what the harm done. A democratic press uses its freedom to strengthen and unify plural democracy, while minimizing harm.

Pragmatic objectivity

In carrying out these two duties, journalists are not neutral chroniclers. They are avid investigators of the facts, but they are not stenographers repeating other people’s alleged facts. They accept the third duty, of pragmatic objectivity—to systematically test the social and political views of themselves, and others.

Those who adopt pragmatic objectivity are engaged journalists who see their norms and methods as means to a larger political goal—providing accurate, verified and well-evidenced interpretations of events and policies as the necessary informational base for democracy. Their stories are not without perspective or conclusions, yet such judgments are evaluated by criteria that go beyond citing specific facts, from logical rigor to coherence with pre-existing knowledge.

“…the third duty, of pragmatic objectivity—to systematically test the social and political views of themselves, and others.”

Pragmatic objectivity recognizes that any code of journalism ethics is based on a more fundamental political and social conception of a good society—in this case an egalitarian and plural democracy. Within this overarching set of values, journalists can go about being as factual, verificational, and impartial in daily practice as they please. But they do not pretend that they are completely neutral, without values and goals. Objectivity is not a value-free zone.

In my book, The Invention of Journalism Ethics, some years ago, I introduced this idea of pragmatic objectivity as a method for testing any form of journalism. My aim was to provide a substitute for the traditional idea of news objectivity as eliminating interpretation and perspective. I believe this conception is now a timely norm for today’s journalism.

Ethics as political morality

In sum, the new social context calls on journalists to clarify their political goals and roles.

In the days ahead, the key issues of journalism ethics will be questions of political morality—the way we think a democracy ought to be organized, and the media’s role in it.

Many journalism conferences focus on practical “tool box” tips, such as using new technology; or, they focus on how to attract audiences through social media.

Yet, when a country enters an uncertain political period, journalists need to return to journalism ethics and political themes, just as such themes arose during the civil rights movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

For many journalists and news organizations, the next several years will be a severe test of their beliefs and ideals—and their will to defend them.

Journalists will not escape the searching question: Why are you a journalist?

Stephen J. A. Ward is an internationally recognized media ethicist, author and educator. He is a distinguished lecturer in ethics at the University of British Columbia, Courtesy Professor at the University of Oregon, and the founding director of the Center for Journalism Ethics at the University of Wisconsin. His book, Radical Media Ethics: A Global Approach, won the 2016 Tankard Book Award.