I’ll go ahead and admit it: In early December, as I finished drafting this “Redefining Engagement” series, I began wondering if I’d missed something big along the way.

“I’m still uneasy about some of the implications of this new [community engagement] paradigm,” I wrote in an email to Peggy Holman, executive director of Journalism that Matters. “If journalists are part of this future, what values/roles do they get to bring with them?”

Since launching the series two weeks ago, I’ve made the case for a type of engaged journalism that rebuilds public trust, amplifies diverse voices and bridges the gap between newsrooms and the communities they serve. I’ve written about promising experiments, like The Listening Post in Macon, Georgia, and The Coral Project’s new online comments tool; explored boundary-pushing ideas, like restorative narrative, inclusive journalism and a redefinition of “objectivity”; and tackled some lingering questions about community engagement, like how will the dollars and cents add up?

But even after 10 stories and 13,000-odd words, this series has yet to broach a pretty central concern: If engaged journalism is going to replace existing routines and practices with new ones, will traditional journalistic values and ethics go out the window too? And if they do, what’s left to warrant calling this thing “journalism” anyway?

My hunch is that I’m not the only classically trained journalist who has struggled with this question. Admittedly, there’s something about community engagement that can seem at once inspiring and a tad unsettling. On the one hand, who can argue with principles like “speak truth to empower” or “nothing about us without us”? For my money, those sound like pretty good values to aim for.

But I’ve also wondered how these values relate to other core principles of journalism. Does “speaking truth to empower,” for example, imply a departure from “speaking truth to power” and the watchdog role it entails? And does “nothing about us without us” mean that journalism’s independent gatekeeping function is obsolete, or that professional news judgement is dead?

So far in this series, I’ve largely sidestepped these thorny questions, choosing instead to highlight examples of engaged journalism in which the role of the capital-J “Journalist” is well defined and the practitioners’ adherence to traditional ethical principles is clear.

But this subject matter permitted no sidestepping, leaving me no choice but to confront the questions I’d been kicking down the road.

To help me navigate this murky intellectual terrain, I turned to two tour guides: Mike Fancher and The Elements of Journalism. Fancher is the former executive editor of the Seattle Times and the founding director of the Agora Journalism Center, and as someone who made his career in the legacy media, Fancher is well-positioned to comment on the movement to reform it.

It was during our interview that Fancher mentioned The Elements of Journalism, the famous book by Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel that outlines journalism’s 10 fundamental principles, forming a kind of ethical guide against which journalists can measure their performance. I’d read Kovach and Rosenstiel’s book as an undergraduate, but needless to say, I was due for a refresher.

So how does engaged journalism impact ethics? Below, I address that question through the lens of the ten elements of journalism, with help from the insights of Fancher and Holman, who together build a compelling case for why community engagement supports, rather than contradicts, the core values of journalism.

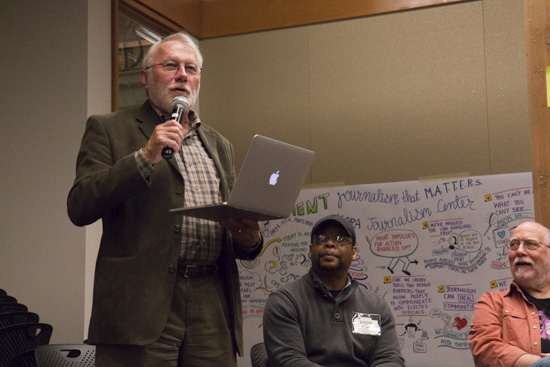

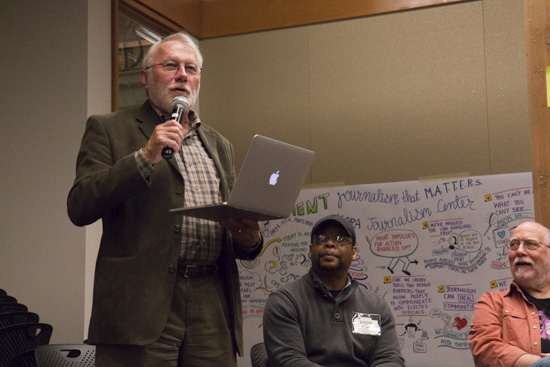

Mike Fancher, former executive editor of the Seattle Times, takes the mic during a group session at Experience Engagement. Photo by Emmalee McDonald.

Journalism’s first obligation is to the truth

The obligation to truth is perhaps journalism’s oldest and most universally honored principle. It’s the reason former NBC anchor Brian Williams lost his job for embellishing the details of his war reporting, and why the public still celebrates remarkable feats of truth-seeking, such as Woodward and Bernstein’s reporting on Watergate.

In engaged journalism, the obligation to truth doesn’t change. What does change is how reporters seek truth. As Fancher explains, engagement provides a powerful defense against the confirmation biases that can influence a journalist’s reporting and storytelling.

“There’s a perception that when journalists go into the community, the people they talk to and the questions they ask are based on their predetermined idea what the story is,” Fancher said. “Engaged journalism is saying, ‘Let’s be open to change our own assumptions about the story, and when we’re seeking truth, let’s try to get in touch with as many people’s truth as we can.’”

So no, engagement doesn’t weaken journalism’s commitment to the truth; engagement only calls for more voices and perspectives to inform it.

Its first loyalty is to citizens

“Journalists like to think of themselves as the people’s surrogate, covering society’s waterfront in the public interest,” Kovach and Rosenstiel explain. “Increasingly, however, the public doesn’t believe them.”

There are lots of reasons for the public’s mistrust, from corporate ownership to the resurgence of partisan news organizations (see: Fox News). But amid these challenges, engaged journalism strikes me as a strategy for winning trust back.

Consider the fact that at the Experience Engagement event, conference organizers didn’t begin by asking how journalism could produce stronger profits or how it could boost audience metrics. Instead, they asked: How can journalism support communities to thrive? This question puts the public interest at the fore and reflects a style of journalism that’s meant to be both with and for the people.

In that respect, Fancher says engaged journalism isn’t something new to journalism, but rather represents a return to one of its fundamental principles.

“A lot of metropolitan daily newspapers embraced the notion that, ‘Hey, we’re your newspaper. We’re here for you,’” he said. “In some ways, this is not as foreign a notion as some people might see it.”

Its essence is a discipline of verification

Skeptics of engaged journalism received some ammunition in 2008 when a user of CNN’s iReport — an experiment in “citizen journalism” — falsely reported that Steve Jobs had died. Several online news outlets picked up the story, Twitter ran wild, and Apple’s stock even dropped, all before Jobs’ family had a chance to deny the erroneous user-contributed report.

The iReport example has been used as a cautionary tale about collaboration between news organizations and the public. But this framing misses the mark. For one, in the age of the 24-hour news cycle, it’s not just citizen journalists who are falling short of journalism’s verification standard. Remember that time when CNN’s John King misreported the arrest of a suspect in the Boston Marathon manhunt, or, better yet, when CNN’s web editors allowed that false Steve Jobs report to be posted on iReport, apparently without double-checking its veracity? Indeed, there are plenty of verification failures these days, and both citizen journalists and professional journalism deserve some of the blame.

But there’s an even bigger reason why the iReport debate has little to say about community engagement: Basically, because it’s not community engagement. It’s audience development, and there’s a huge difference.

For example, in a recent iReport article, CNN editors invited users to submit videos showing their preferred method for popping bubble wrap, along with the promise that “your video could be used on Jan. 25th, which is Bubble Wrap Appreciation Day.” Believe it or not, when community engagement advocates talk about inclusive journalism and participatory media, that’s not exactly the kind of engagement they have in mind.

At its best, engaged journalism is about creating news structures that support collaboration between journalists and communities. That means finding ways to amplify community voices through reporting and storytelling. It doesn’t mean outsourcing responsibilities such as verification or news judgment to the public, Fancher says.

“No, journalists are still in the core of the conversation,” he explained. “We just need to have more people included in that conversation.”

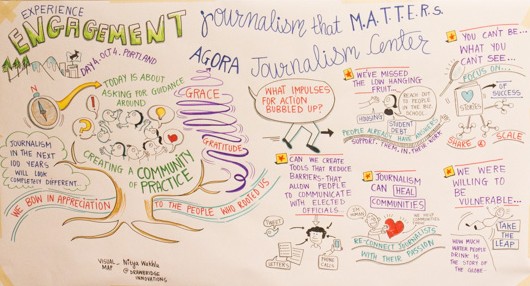

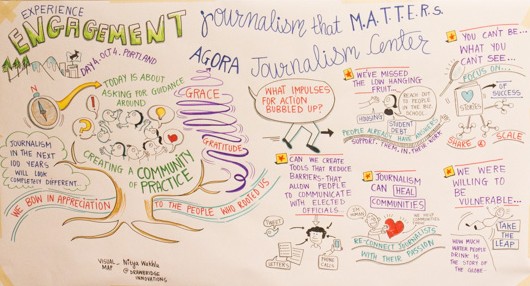

Part of a visual map illustrated by Nitya Wakhlu Experience Engagement. Photo by Emmalee McDonald.

Its practitioners must maintain an independence from those they cover

There’s no shirking the fact that the independence principle appears decidedly at odds with the tenets of engaged journalism. According to the community engagement paradigm, journalism works best when it involves collaboration with community, a networked process in which journalists and community members are interdependent.

The question here isn’t whether engaged journalism brings the independence principle into flux. It does. The question is whether that’s a bad thing — and whether, in the digital age, journalism has any other choice.

“The traditional mission of journalism has been to provide people the news and information they need to be free and self-governing,” Fancher said. “The problem with that is the word ‘provide.’ We live in a world that’s much more interactive now, and people are not satisfied to be passive consumers of news and information. They want to share information, they want to create information, they want to be more involved in the process of determining what matters in their lives and in their communities.”

In this interconnected world, it seems that the notion of independence might need a facelift. And perhaps that begins by distinguishing independence from detachment. As Kovach and Rosenstiel explain: “Editorial independence has over time begun, in some quarters, to harden into isolation. As journalists tried to honor and protect their carefully won independence from party and commercial pressures, they sometimes came to pursue independence for its own sake. Detachment from outside pressure could bleed into disengagement from the community.”

Engaged journalism can help combat isolation, and that’s a good thing. The hard part is figuring out how to balance the principle of independent journalism with the realities of an interdependent world.

“That’s what we’re wrestling with,” Fancher said. “But I think it’s a legitimate conversation for journalists to engage in.”

It must serve as an independent monitor of power

In December, as I finished drafting the Redefining Engagement series, this is the principle I couldn’t get off my mind. As I wrote in an email to a colleague: “The thorny question that remains is how the watchdogs, with their sharp teeth, and the community weavers, with their empathetic powers of listening, can coexist within the new journalism.”

Indeed, “community weavers” appear to serve a very different function than public-accountability watchdogs. For one, their disposition is cooperative, not adversarial, and their mission is less about “afflicting the comfortable” than about “comforting the afflicted.”

Holman says this philosophical pivot could help reverse the finger pointing, foot stomping and political shouting that pervade modern civic discourse.

“When people shout, it’s because they don’t feel heard,” she explained. “The point of community engagement is to create a space in which people who see the world differently hear each other.”

It’s an aspirational notion, but also one that raises questions about journalism’s relationship to power. For example, if the community weaver’s role is to bring people together, do we include elected officials, government bureaucrats and corporate CEOs in that mix? If so, what are the implications? Can journalists forge more trusting, empathetic relationships while still using their sharp elbows to hold the powerful accountable?

These are tough, even uncomfortable, questions. But it’s worth remembering that engaged journalism doesn’t call for us to all hold hands and sing “kumbaya” together. Rather, engaged journalism is about listening to community members and their concerns, honoring and amplifying their voices, and strengthening their capacity to engage with one another and with the public officials who represent them.

When Holman and the co-authors of Experience Engagement’s developmental evaluation talk about fostering a “civic communications ecosystem,” I think that’s what they have in mind. And, as Fancher explains, that vision is consistent with the main reason why independence from power emerged as a principle in the first place.

“The purpose,” Fancher said, “was to help journalists avoid conflicts of interest where they’d be serving some vested interest other than the public’s interest. The purpose was to be able to say to the public: ‘We stand for you above everything else.’”

Peggy Holman joins a discussion at Experience Engagement. Photo by Emmalee McDonald.

It must provide a forum for public criticism and compromise

The notion of a civic sphere dates all the way back to the ancient Greeks, and it remains at the heart of engaged journalism. Indeed, as noted above, Experience Engagement’s developmental evaluation explicitly outlines the need for a “civic communications ecosystem” that would “provide robust information, feedback, inclusive dialogue, strategy and action for serving community goals.”

That vision shares much in common with Kovach and Rosenstiel’s description of the civic forum, which similarly calls for journalism to impart trustworthy information, serve all parts of the community (“not just the affluent or demographically attractive”) and help steward compromise in order to support collaborative solutions.

Holman says an example of this approach at its very best comes from Canada in 1991, when the newsweekly Maclean’s brought together 12 people specifically chosen for their differences and tasked them with reaching a consensus vision for the country’s future.

For two-and-a-half days, with Canadian TV filming the whole thing, the 12-person sample group worked with a pair of conflict resolution experts to move beyond their differences and find common ground. The resulting document, dubbed “The People’s Verdict,” was published as part of a 40-page feature in Maclean’s, and the documentary footage aired as an hour-long special on Canadian television.

Notably, this application of engaged journalism sparked lively dialogue among readers and viewers, as well as town hall meetings that addressed issues raised by the project. In other words, Holman says, it helped support a civic sphere.

“This narrative trajectory enabled millions of viewers to vicariously experience this different kind of conversation and its power in dealing with normally divisive public issues,” she explained. “It helped trigger months of conversation around Canada and offers us guidance in how to magnify the impact of such ‘mini-public’ conversations up to society-wide scale.”

It must strive to keep the significant interesting and relevant

According to Kovach and Rosenstiel, journalism is essentially a two-step process: “The first challenge is finding the information that people need to live their lives. The second is to make it meaningful, relevant and engaging.”

Engaged journalism would appear to support both objectives. When journalists listen to communities, they better understand the information and issues that matter to people’s lives. And when journalists put community voices and stories at the heart of their work, rather than amplifying political bluster, the result, I would argue, is a more meaningful and engaging news product.

However, despite this apparent compatibility, Kovach and Rosenstiel’s eighth element of journalism is one that advocates of community engagement are sometimes guilty of neglecting. The problem: In the well-intentioned effort to make media more participatory and inclusive of diverse voices, there’s a tendency to undervalue the journalist’s craftsmanship and professional news judgement.

At Experience Engagement, for example, one interviewee suggested that journalists should really be asking themselves, “How do we get out of the way so that people can tell their own stories?”

I think the bigger point being made is that journalists should do a better job giving communities a stake in their own representation. However, there’s a lot of distance between honoring authentic community voice and simply handing over the keys. The latter approach neglects the expertise of journalists, and it seems likely to produce storytelling that — however authentic — would be less well crafted, less compelling and ultimately less interesting to a mass audience.

So sure, journalism needs to fix its record of parachuting into marginalized communities and misrepresenting their experiences and perspectives. But as Fancher explains, engaged journalism still needs to put journalists at the heart of the storytelling process, and it still needs to value the sensibilities and skills that make journalism a professional craft.

“This is not an approach that says ‘We’re going to stop being journalists and start being something else,’” Fancher said. “It’s an approach that says, ‘We’re going to be better journalists.’”

It must keep the news comprehensive and proportional

“Traditional news routines privilege the voices of politicians, official spokespeople and perceived ‘policy experts,’ while largely marginalizing community stories. This norm explains why people in positions of power often dictate civic discourse — and why news coverage tends to focus on presidential candidates’ xenophobic immigration proposals and fear-mongering war cries instead of on, say, how immigration policy impacts the children of undocumented immigrants.”

In my post on deep listening, that’s how I framed the need for news routines that empower communities, rather than politicians, to set the agenda. This tenet of engagement journalism mirrors Kovach and Rosenstiel’s call for comprehensive and proportional news coverage that reflects the broad scope of community life.

In fact, the need for engaged journalism is largely a symptom of the media’s failure to honor this principle. Amid dwindling budgets and strained resources, news organizations have too often been content to report primarily on political campaigns and other institutions of power, instead of putting community life at the heart of their coverage. Engaged journalism requires a rebalancing of the scales.

As Fancher explains, “If there’s a paradigm shift here, it’s that we have tended to think of the newsmakers as being institutions and people who are designated as leaders of communities. That doesn’t change, but it’s not complete. We need to be in the communities to understand their lived experience and to and help them tell their story to the policymakers and to the decision makers, so that the policies relate to what people want to talk about.”

Regina Lawrence, director of the SOJC’s George S. Turnbull Portland Center, participates in an activity at Experience Engagement. Photo by Emmalee McDonald.

Its practitioners must be allowed to exercise their personal conscience

This principle of journalism is under attack in the American media — but not by community engagement. As journalists were reminded last month when casino mogul Sheldon Adelson’s family purchased the Las Vegas Review-Journal, the real threat is partisan ownership and the age-old quandary of self-preservation.

Consider this: In December, following Adelson’s surprise decision to purchase the newspaper, editor-in-chief Mike Hengel resigned amid concerns that Adelson — a billionaire conservative philanthropist — would attempt to use his ownership stake to influence the paper’s coverage. Similar concerns arose in 2007 when News Corp., the company owned by controversial media magnate Rupert Murdoch, took control of the Wall Street Journal.

But the most damning sign of trouble broke last month, on Christmas Eve, when career-long reporter Steve Majerus-Collins announced his resignation from The Bristol Press in a passionate and pointed Facebook post. Majerus-Collins cited the ethical disregard of his editor and publisher, Michael E. Schroeder, who allegedly used a false byline to publish a bogus story in support of a political ally.

“A newspaper editor cannot be allowed to stamp on the most basic rules of journalism and pay no price,” Majerus-Collins wrote in his post. “He should be shunned by my colleagues, cut off by professional organizations and told to pound sand by anyone working for him who has integrity. So I quit.”

Engaged journalism might not alleviate the problem of unethical meddling by management, but it certainly wouldn’t hurt. As outlined above, the community engagement approach is consistent with journalism’s core values of truth-seeking and loyalty to the public, and it has no more room for influence-peddlers than do principled reporters like Majerus-Collins.

Citizens, too, have rights and responsibilities when it comes to the news

This principle, added to The Elements of Journalism’s latest version, reflects the reality that contemporary digital technologies have blurred the distinction between citizen and journalist. As the American Press Institute explains, “Writing a blog entry, commenting on a social media site, sending a tweet, or ‘liking’ a picture or post, likely involves a shorthand version of the journalistic process. One comes across information, decides whether or not it’s believable, assesses its strength and weaknesses, determines if it has value to others, decides what to ignore and what to pass on, chooses the best way to share it, and then hits the ‘send’ button.”

In this digital sphere, legacy media’s gatekeeping power is disappearing. But what has begun to replace it is an equally vital sensemaking function. Given the seemingly endless flow of news and information online, journalists are now charged with providing “citizens with the tools they need to extract knowledge for themselves from the undifferentiated flood or rumor, propaganda, gossip, fact, assertion and allegation the communications system now produces.”

This new sensemaking role is consistent with the idea that journalism should be a collaboration with communities. As addressed above, the move toward collaboration doesn’t mean creating insular pages on a news site where “citizen journalists” can post unverified, unfiltered news reports without the benefit of professional news judgement and craftsmanship. Rather, it means journalists should find ways to work with community members — in their reporting, in their storytelling, in their distribution and in their engagement — to uncover the news and information required to sustain a free and self-governing society.

The callout to skeptics

This article began with a question about whether traditional ethics and values would persevere — or disappear — with engaged journalism. And it wasn’t a rhetorical question. When I sat down to start writing, I still had real concerns about the broader implications of this new approach. Would community engagement require tradeoffs? If so, what would journalism gain from its collaboration with communities? What would it lose? And how would we decide if the tradeoffs were worth it?

These questions are far from settled, and it seems important to keep them at the heart of the reform movement, where they can be openly discussed and debated.

But it’s also important to acknowledge that a conversation strictly among the converted is unlikely to yield progress. This debate needs the voices of the skeptics, those who either don’t see their work valued in the paradigm of engaged journalism or who don’t believe that such sweeping reform could ever actually happen.

This article, then, is an invitation for the skeptics to push back and poke holes in the case for community engagement. That’s how the conversation will move forward. That’s how the hard questions will get answered. That’s how we’ll produce better journalism and a stronger democracy.

At the Agora Journalism Center, we hope this series has been a step in that direction. Now we invite the skeptics to take the next one.

This post originally appeared as part of a series on MediaShift. It is republished here as part of an agreement.

“Redefining Engagement” is a special 11-part series on the progress, promise and potential challenges of community engagement in journalism. The series, produced by the Agora Journalism Center, will be published in serial this month by MediaShift. Click here for the full series.

Ben DeJarnette is the associate editor at MediaShift. He is also a contributing writer for the University of Oregon School of Journalism & Communication’s Agora Journalism Center, the gathering place for innovation in communication and civic engagement. On Oct. 1-4, 2015, the Agora Journalism Center and Journalism That Matters partnered to host Experience Engagement, a four-day participatory “un-conference” in Portland, Oregon. Journalism That Matters has been hosting breakthrough conversations about the emerging media ecosystem for more than 15 years.