In the spring of 2019, former members of the Association of Opinion Journalists reunited in Madison, Wisconsin. The group, which merged in 2016 with the American Society of News Editors (now the News Leaders Association), was once 600 members strong.

Before its membership dwindled to fewer than 200 members and it could no longer sustain itself as a separate non-profit organization, AOJ was the only professional organization dedicated to editorial advocacy and holding the highest professional standards of fairness, accuracy, intellectual integrity and service to the public interest.

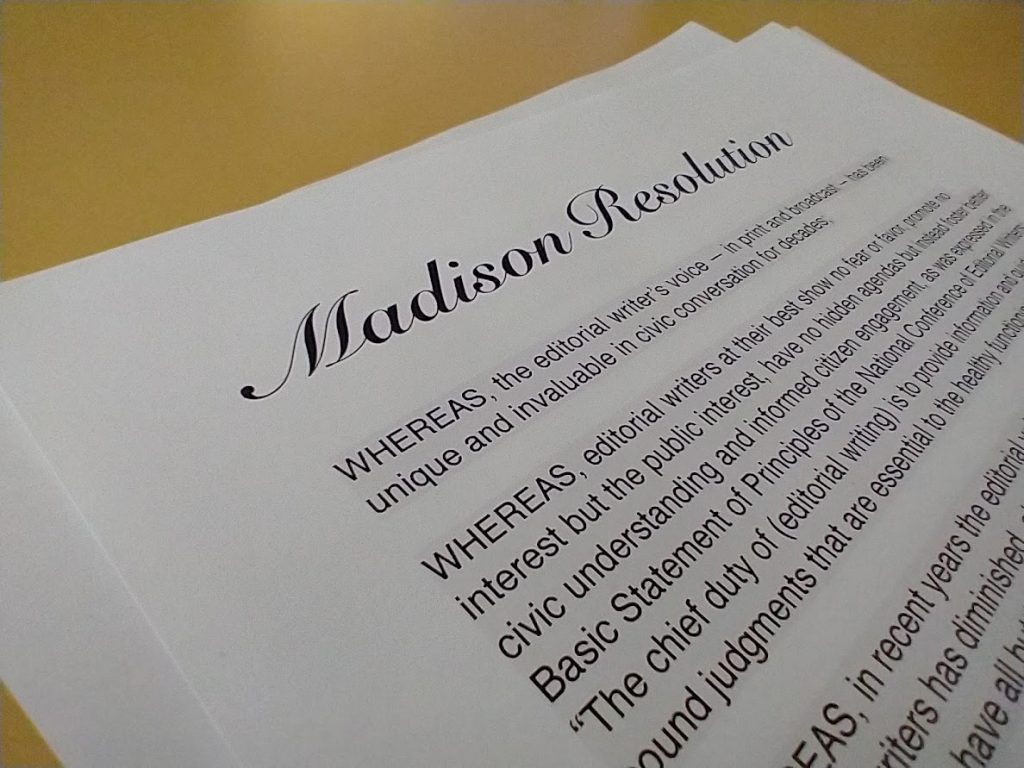

This reunion of members produced the Madison Resolution, a promise to continue to promote editorial writing and ensure editorial and opinion writing continues to play a “vital role in journalism, in civic life and in our democracy.”

Indeed, opinion journalism fulfills many functions in American journalism and democracy. Though research on opinion journalism is limited, scholars have suggested that opinion journalists help to evaluate, contextualize and explain the news in ways traditional news reporters may not have the capacity to do. Without opinion journalism, people lose a resource that helps them make sense of what is happening in the world, their country and their community.

In local news, the opinion section of a newspaper was once a vibrant crossroads of debate, discussion, and community engagement. It was a place where opinion journalists could explore important topics and readers could engage with opinion journalists and each other. Now, as newspapers decrease their editorial staff and output, their capacity to provide such dialogue is limited.

In its stead comes less localized content — letters by public officials and advocacy groups or syndicated opinions on national politics, for example. Local communities lose a mediated forum to debate, discuss and understand the civic issues that matter to them most. Some turn to the cacophony of social media to try to understand the news of the day.

With our media environment in flux, what will it take to make good on the Madison Resolution?

The death of the Association of Opinion Journalists is emblematic of a greater trend in journalism. According to Pew Research Center, newsroom employment at U.S. newspapers decreased by about 50 percent since 2008 and the trend continues as the news industry grapples with economic strains caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. As newsroom staffs shrink, opinion journalists are often quick to go, leaving a significant gap in the pages — in print and online — of local newspapers. This change comes at a time of increasing mistrust and hostility toward news media and, “a cacophony of opinion, bias and vitriol, and corrosive partisanship,” as outlined in the Madison Resolution.

David Haynes, former opinion writer and current Ideas Lab editor at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, attributes some of this change to media fragmentation and social media.

“Social media and media fragmentation have changed the game for all journalists, whether they write opinions or not,” Haynes says. “Fragmentation means legacy media like newspapers have somewhat less influence than in the past — there are simply a lot of places you can go for information.”

And yet, it may not feel like there is a shortage of opinion in America’s current media landscape, according to Sewell Chan, the editorial page editor of the Los Angeles Times.

“In our hyperpolarized time, it seems sometimes as though there are too many opinions. But in fact, there is not enough thoughtful opinion writing …”

Sewell Chan, Los Angeles Times

“In our hyperpolarized time, it seems sometimes as though there are too many opinions,” Chan says. “But in fact, there is not enough thoughtful opinion writing — opinion writing that takes into account the complexity and ambiguity of all human affairs; that is empathetic toward people who disagree, and that truly adds insight and perspective. We need [this] high-quality opinion journalism more than ever.”

The high-quality opinion journalism Chan describes can advocate and eventually lead to tangible change in the communities for which it is written.

Fred Fiske, past president of the Association of Opinion Journalists and the former editorial page editor of the Post-Standard in Syracuse, New York, said their opinion journalism on the rights of people with disabilities helped lead to mainstreaming special education students in Syracuse schools.

“It’s not like we reformed the government or anything,” Fiske says. “But I like to think we made a difference.”

Fiske says that when a newspaper has an active editorial section, it leads to vibrant civic life within a community. These observations are supported by empirical evidence showing that when local newspapers decline, people consume more nationalized journalism, are less informed about their local government and become more polarized.

Declining trust in journalism means that clearly labeling opinion content has also become more important. Research by the Duke Reporters’ Lab found readers are often confused about what content is hard news versus what content is opinion. Though opinion journalists often use conventional reporting techniques in their work, they are paid to opine — knowing the distinction between the two could increase trust in newspapers and help with the survival of local opinion journalism.

Colleen Nelson, the national opinion editor for McClatchy and editorial page editor for the Kansas City Star, also emphasizes the importance of speed and relevance. Though her content separates news from opinion she challenges her opinion writers to mimic conventions of hard reporting. She wants her opinion journalists to be faster and keep up with the speed of the news cycle to give their readers the content they want when they want it.

“We’ve asked folks to move more quickly … it’s okay to break news in an editorial or a column.”

Colleen Nelson, National Opinion Editor for McClatchy

“The old-fashioned way of doing opinion journalism was that something happened, the newsrooms reports on it, the opinion journalists sit around and think deep thoughts for a couple of days, and eventually come out with their opinion,” Nelson says. “That doesn’t work in the current news cycle. We’ve asked folks to move more quickly … it’s okay to break news in an editorial or a column.”

Jessie Opoien, the opinion editor of The Capital Times, also noted the importance of moving quickly — of staying ahead of the game and being proactive and thoughtful about what readers are looking for.

To break news using opinion journalism, and to create good opinion journalism more generally, original reporting is essential. Though Nelson’s opinion writers do often rely on reporting from the newsroom, it is not enough to repeat the news that has already been reported and tack an opinion on to the end. Nelson wants her writers to have a strong opinion, but also to tell readers something that they don’t already know.

Opoien echoes this sentiment.

“It’s a valuable service to not lose sight of the things that made you a solid journalist when you were reporting,” she says.

Another valuable method of revitalizing opinion journalism is localizing a newspaper’s opinion content. At McClatchy papers, Nelson’s opinion teams have focused on endorsing candidates for local office. They conduct interviews with the candidates, do original reporting on them and additional research. She’s found readers specifically subscribe so they can read those endorsements because they contain information readers cannot find anywhere else.

The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel localizes their content as well but goes a step further by blending their opinion content with solutions journalism in their Ideas Lab. Originally, the goal with the Ideas Lab was to publish solutions journalism, as solutions-oriented stories see more engagement.

Haynes says news organizations must publish content that serves their various communities or they will not survive. In an election year in the middle of a pandemic, people have a lot to say, so the Ideas Lab continues to be a hybrid section of solutions and opinion journalism, with the opinion clearly labeled.

“Our goal with the opinion section was always to provide a place where people could convene and consider the issues of the day.”

David Haynes, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“Our goal with the opinion section was always to provide a place where people could convene and consider the issues of the day,” Haynes says. “We still do that now with this hybrid approach.”

Fiske says he would focus on novel funding mechanisms in order to ensure the future of opinion journalism. He proposes setting up foundations whose proceeds would hire editorial writers and set them up to work in local communities.

“Once again [communities] can have a narrative of advocacy about daily life in their city,” Fiske said. “Get them an endowed editorial chair at each newspaper — that’s my idea, but no one’s jumped on it.”

Though the approach of the McClatchy papers, The Cap Times, and other newspapers across the country differ, the goal of opinion journalists stays the same, Opoien says.

“There’s a responsibility to serve the community or at least offer a space where those community conversations can happen, and in a way that is more structured and civil.”

Jessie Opoien, The Cap Times

“There’s a responsibility to serve the community or at least offer a space where those community conversations can happen, and in a way that is more structured and civil,” she says.

This type of opinion journalism — journalism that serves the community, shows empathy for the readers and respect for those who may disagree — is invaluable for readers in a democratic society.

Funding, resources and the effects of social media and media fragmentation persist and are likely to continue to change the media landscape, including the roles and responsibilities of opinion journalists. Still, through innovation and localization, many are optimistic about what’s to come.

“Opinion journalism can have a positive future if we make clear its value to communities and relentlessly focus on getting the facts right,” Chan says.

The Center for Journalism Ethics encourages the highest standards in journalism ethics worldwide. We foster vigorous debate about ethical practices in journalism and provide a resource for producers, consumers and students of journalism. Sign up for our quarterly newsletter here.