Photo: Steven Potter

Journalists incorporate data into their reporting for good reason: numbers tell us important, odd and interesting things about ourselves.

Hidden within raw data are insights about our patterns, problems and trends, such as the frequency of our activities, crime levels, how we distribute goods and services, where we have pockets of poverty or wealth, how we use our time and countless other measurable facts.

But as more journalists begin to lean on data as a reporting tool, they need to keep a keen eye on just how effectively — and ethically — they’re using it.

Rodrigo Zamith, an assistant professor of journalism at University of Massachusetts Amherst, does just that.

“[Data-based journalism] has become discursively valuable because a large group of people still — incorrectly, in my mind — view [it] as being more neutral and objective than traditional journalism,” Zamith says. “As a social scientist, I view data journalism as an opportunity to further imbue some of the best practices from science into journalism in order to make journalism more transparent and informative.”

His most recent study, however, found that journalists at two of the country’s biggest and most-respected newspapers were not being as transparent and informative with data as they could have been.

In his study “Transparency, Interactivity, Diversity, and Information Provenance in Everyday Data Journalism” (Digital Journalism, 2019), Zamith found that both The New York Times and The Washington Post failed to be completely transparent about the data they used, often didn’t explain their data collection or analysis methods and usually didn’t give the public access to the data they used in their reporting.

Zamith discussed his study’s findings and the ethics involved in data journalism recently with the Center for Journalism Ethics.

This interview has been edited for length.

What are the ethical concerns involved in data journalism and data-driven reporting?

At the top of my list is probably not taking advantage of this special status that some people grant to quantification. Stories that involve data analysis are often viewed as being more credible, and it can be tempting for a journalist to leverage that perception in order to appear more authoritative or precise. To be clear, I don’t think most data journalists intentionally do this but they certainly could. Moreover, simple misunderstandings of data borne from deadline pressures or lack of training can result in improper interpretation and contextualization, which is a more common problem.

Second, data journalists can sometimes gain access to information that would violate individuals’ expectations of privacy. This sometimes comes via individual-level data that haven’t been de-identified or through de-identified data that can become easily identifiable when combined with other datasets. The desire to be transparent and forthcoming — such as by creating databases or interactive visualizations that allow viewers to explore individual-level data points — sometimes violates the ethical objective of minimizing harm.

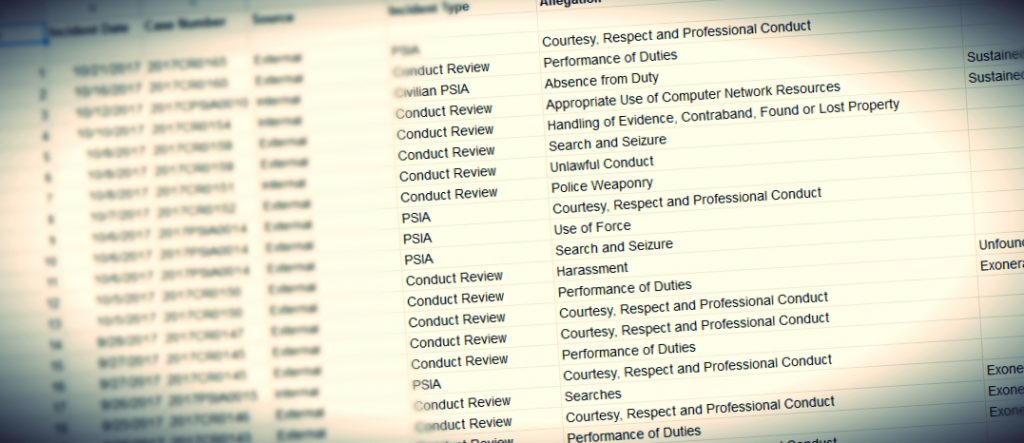

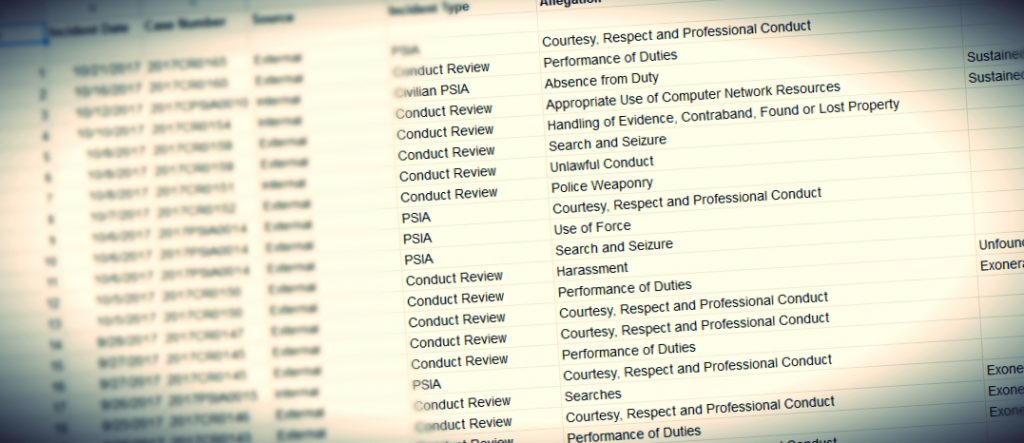

Third, data journalists often use data from other (non-news) organizations, and it is crucial that they remain mindful of those organizations’ objectives and potential biases in order to ensure the journalist is reporting truthful (and not just ‘accurate’) information. Journalists don’t often have the luxury of choosing from multiple datasets that seek to measure the same things. Rather, they may have to decide whether a dataset is simply “good enough” — and, in some cases, the available data is worse than having no supporting data at all. These ethical concerns only begin to scratch the surface, though. Data journalism, and journalism in general, is a challenging endeavor.

What did your recent study, “Transparency, Interactivity, Diversity, and Information Provenance in Everyday Data Journalism,” reveal about the practices of data journalism by the New York Times and The Washington Post?

The big takeaway from the study is that the potential many scholars and practitioners see in data journalism are not yet being realized in the day-to-day data journalism produced by The New York Times and The Washington Post. Specifically, the study found that those organizations favored “hard news” topics, typically used fairly uncomplex data visualizations with low levels of interactivity, relied primarily on institutional sources (especially government sources) and engaged in limited original data collection, and were far less transparent than one might hope for in terms of linking directly to datasets or detailing the methodologies used for analysis.

While that may seem like an indictment of their performance, that is not at all what I mean to convey with my study. The study measured their day-to-day work against an ideal — a rather high bar — and I believe there are legitimate structural factors that can help explain the shortcomings I pointed to. I actually think these two organizations do a good job in many regards, and my hope is to see them do even better in other areas.

Why is this lack of transparency and failure to explain methodology exhibited by the Times and Post ethically problematic?

One of the key tenets of the Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics is to “be accountable and transparent.” This involves explaining to readers the key processes underlying a story, including where the information came from and how the information was analyzed.

My study found that the Times and Post rarely linked directly to the datasets they used. However, they did often link to the organizations they got the information from. The issue is that it can sometimes be hard to find a specific dataset even after being pointed to an organization’s homepage. Thus, if the ethical objective is transparency, data journalists are only partly succeeding.

I believe data journalists should aim to make it as easy as possible for readers to double-check the journalist’s work and perhaps even to build on the journalist’s work. To achieve that, a direct link is preferable. This is especially important if the data journalist has altered the original data in any way, such as by aggregating data or calculating new variables, since it introduces new possibilities for human error and biases. In those cases, sharing their edited datasets is one way to adhere to the transparency objective.

My study also found that journalists seldom provided methodological details separately from an article, such as in methodology boxes at the end of the article, in footnotes that need to be clicked on to appear, or in separate articles devoted to detailing the methodology. While we did not directly measure the inclusion of those details within the article, it is rare to find them there because journalists often view themselves as storytellers and such detail can bog down the narrative.

The lack of methodological details is problematic, though, because it again fails to deliver on the transparency objective. Datasets don’t just produce errors if they’re analyzed incorrectly. They would just tell a story that misinforms. Being clear about one’s methodology provides an avenue for accountability so others can review and, if necessary, critique the journalist’s analytic choices. One of the great hopes for data journalism is that it will help increase trust in journalism precisely because of its many avenues for increasing transparency. Failing to make the data easily accessible or clearly explaining the methodology reduces the likelihood of realizing that hope.

What should these two outlets do to correct these missteps?

I think the data journalists at those organizations, and many others, generally do a good job. I also think that the shortcomings I identified are partly byproducts of journalistic conventions.

For example, the dearth of links to specific datasets isn’t terribly atypical if you consider the traditional analogue: news organizations are more likely to link to the institution affiliated with a human source rather than to the source’s biography page. I don’t think this is an unreasonable practice but I do think that it is a practice that can be adjusted to take advantage of the distinct affordances of data journalism. After all, a human source may not have a publicly available biography page but the data journalist will always have the dataset.

If the dataset is already publicly hosted, it should be easy to link directly to it, perhaps in addition to linking to the parent organization. If it is not already publicly hosted, the data journalist may be able to upload it to any of the many open data hubs out there, and link directly to that. If they’d like a little more control, news organizations should invest in the technical infrastructure for self-hosting datasets. Having said that, there are instances where it is inappropriate to put up a dataset, as in cases where it may violate copyright or a reasonable expectation of privacy. In such cases, journalists should just explain that decision.

I believe the oftentimes inadequate methodological explanations can also be attributed to journalistic norms. Journalists are tasked with simplifying things and writing in an accessible manner, which can promote doing away with technical and methodological details. I think it’s very reasonable and perhaps even a best practice to offload that information to a section separate from the article, provided it’s made clear to a reader how those details may be accessed.

However, writing up those details can be rather time-consuming, presenting a challenge to journalists constantly being asked to do more with less. This is doubly true for the day-to-day data journalism that likely won’t be nominated for prestigious awards. This would require a broader cultural shift within organizations to value this kind of work, which doesn’t typically provide immediate and easily measured benefits. However, it is important work. For the majority of people, who may not fully understand the technical details or have the inclination to evaluate them, the perception of greater transparency increases their trust in the news story and the news organization. For the minority, it allows them to scrutinize and perhaps even suggest corrections to the journalists. And we should celebrate those instances because it means that better, more trustworthy journalism is being done.

With ethics in mind, what are the guidelines and best practices that journalists should follow when working with data?

To better realize the ideal of transparency, data journalists should keep and make public reproducible analysis documents that detail how they analyzed their data. Many data journalists already keep a data analysis notebook, so they’re off to a good start. However, a best practice would be to post the original and modified datasets, as well as the analysis scripts, on platforms like GitHub. In fact, The New York Times and The Washington Post already do this with some of their projects, and they deserve credit for that openness. They’re not the only ones, with outlets like The Boston Globe, FiveThirtyEight and BuzzFeed News doing the same. My hope is that such practices can be extended to the day-to-day data journalism — even if it is not as well-documented as the bigger projects.

Over time, this would hopefully become the norm rather than the exception. However, it requires news organizations to recognize, incentivize, and reward that kind of behavior. Data journalists should also make clear in the body of a story the limitations of their datasets and analyses. It can sometimes feel like such details bog down a story or make it appear less authoritative. However, they’re crucial for ensuring a reader is well-informed, which is ultimately a key purpose of journalism.

What are your expectations for data journalists going forward? How can they use data in an ethical manner?

It is my hope that data journalists will collect more data themselves, or perhaps collaborate in that endeavor. My study found that The New York Times and the Washington Post rarely collect their own data for their day-to-day data journalism, and consequently rely on third-party data that generally comes from government sources but also from different nonprofits and interest groups. That’s not surprising because it’s expensive and time-consuming to collect primary data though there are several examples of news organization doing that for bigger projects.

Nevertheless, there are a large gaps in data collection at the moment, and partnerships between news organizations and academic institutions or civic groups may yield important and timely stories that shed light on important truths within and across communities.

I also think data journalists need to become even more careful with data subsidies going forward. I expect data journalists will be increasingly targeted by unethical individuals and organizations that publish data as a strategic communication tool because they understand that citizens tend to find numbers more authoritative than personal stories. Combating that would require data journalists to become even more adept at evaluating data quality and methodologies. We have many accomplished experts who specialize in data literacy, and it’s important that we get their insights into as many newsrooms as possible.

Finally, I expect data journalism to become even more interdisciplinary in the coming years, with the likes of graphic designers and programmers being more tightly integrated with the editorial side in order to not only “support” data journalism but actively co-produce it. Some news organizations have moved more quickly than others in this direction, and I believe it is an important move to advance the most ethical version of data journalism.

What will you be studying next and what ethical issues might you encounter with it?

I view this study as an opening act because it leaves important questions unanswered. For example, the study’s design limits its ability to answer the “why” questions, such as why specific affordances, like information boxes provided at the end of an article to explain methodological choices, are not commonly utilized. Of particular interest to me is the use different collaborative platforms like GitHub to further “open” journalism, and the extent to which the transparency ideal becomes contested in the minds of journalists who use those platforms. As part of a separate line of research, I would also like to explore the third-party algorithms and tools being adopted by journalists, and how the designers of those tools — many of whom have limited, if any, journalistic background — attempt to engineer greater acceptance of their tools among journalists. I expect that line of research to directly engage with ethical tensions that emerge from the clash of different professional logics, as well as tensions that arise in the merging of commercial and public-service interests.

The Center for Journalism Ethics encourages the highest standards in journalism ethics worldwide. We foster vigorous debate about ethical practices in journalism and provide a resource for producers, consumers and students of journalism. Sign up for our quarterly newsletter here.