Director of the Center for Journalism Ethics Kathleen Bartzen Culver talks with keynote guest and leading tech journalist Kara Swisher at the Center’s conference What #MeToo Means for Gender, Power & Ethical Journalism on April 26 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

More than 160 people attended the Center for Journalism Ethics conference on April 26, 2019, with an additional 435 views occurring via livestream.

Focused on “What #MeToo Means for Gender, Power & Ethical Journalism,” the conference featured a keynote conversation with leading tech journalist Kara Swisher, as well as expert panelists from leading news organizations and universities all over the country.

In the keynote discussion with Center director Kathleen Bartzen Culver, Swisher discussed the beginnings of her career. As a student at Georgetown University, Swisher called the Washington Post to complain about their coverage of a Georgetown event, a complaint that ultimately led to a job offer.

At the Washington Post, Swisher covered the Internet early on.

“I saw it as the printing press, television, radio. I saw early on what it meant for journalism. I knew this was going to change everything,” Swisher said.

Students respond to keynote Kara Swisher’s address.

She said that being a good beat reporter and covering tech news through a personal lens, rather than technical, helped distinguish her in the beginning of her career.

Swisher described the way she covers tech as this, “I won’t tell you how a watch works, but I’ll tell you the time.”

The conversation transitioned to the topic of #MeToo, with Swisher pointing out that #MeToo stories were hiding in plain sight.

She said that when she started covering it, the most interesting part was that most men didn’t know about it. She points to all-male editorial boards as a possible reason for why these stories took so long to come out.

She said that once the reporting came about, it was people who had been unsafe themselves who covered the #MeToo stories – women, people of color and LGBTQ+ people.

She discussed how hard it is to ask people to go public with their stories and how hard it is to ask people to do things that might hurt them.

Swisher next discussed three “tragedies” in the current tech workplace.

The first is a lack of self-awareness and reflection. Next, believing that money equates social good. Finally, having the inability to empathize with people who are not like you.

She also touched on likeability – and the fact that she doesn’t care about being likeable.

“You don’t want to be a jerk, but when you don’t have to be the good girl, it’s freeing,” Swisher said.

“Just say things. Don’t hear no. You have to be disputatious but polite. There isn’t actually a cost. The cost is going along with things. The cost is waiting until later.”

Panel 1: The Power of Portrayals in a Wired World

Linda Steiner and Negassi Tesfamichael

- Tracy Lucht (moderator), associate professor, Greenlee School of Journalism and Communication at Iowa State University

- Barbara Glickstein, director of communications, Media Projects at the Center for Health Policy and Media Engagement at George Washington University School of Nursing

- Kem Knapp Sawyer, contributing editor, Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting

- Linda Steiner, professor, Philip Merrill College of Journalism, University of Maryland

- Negassi Tesfamichael, education reporter, The Cap Times

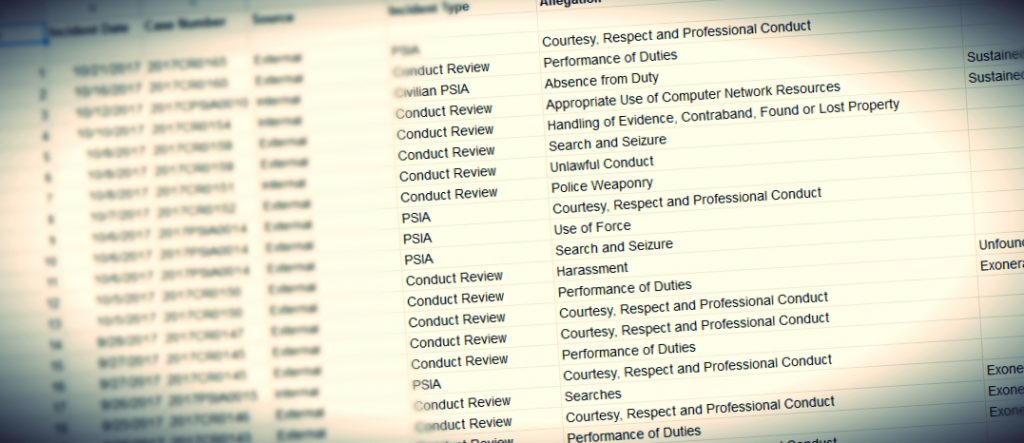

This panel focused on covering stories related to #MeToo, along with how to prepare journalists to cover those stories in the future.

“I don’t think I’m surprised anymore. I think what I’m surprised about is when people are surprised,” Glickstein said.

Steiner discussed that the sheer number of women who have been willing to tell their stories and be named is surprising, and it has encouraged others to come forward as well.

“There’s something about the invasion of one’s body that makes it difficult to talk about, even if we think we’re tough,” Steiner said.

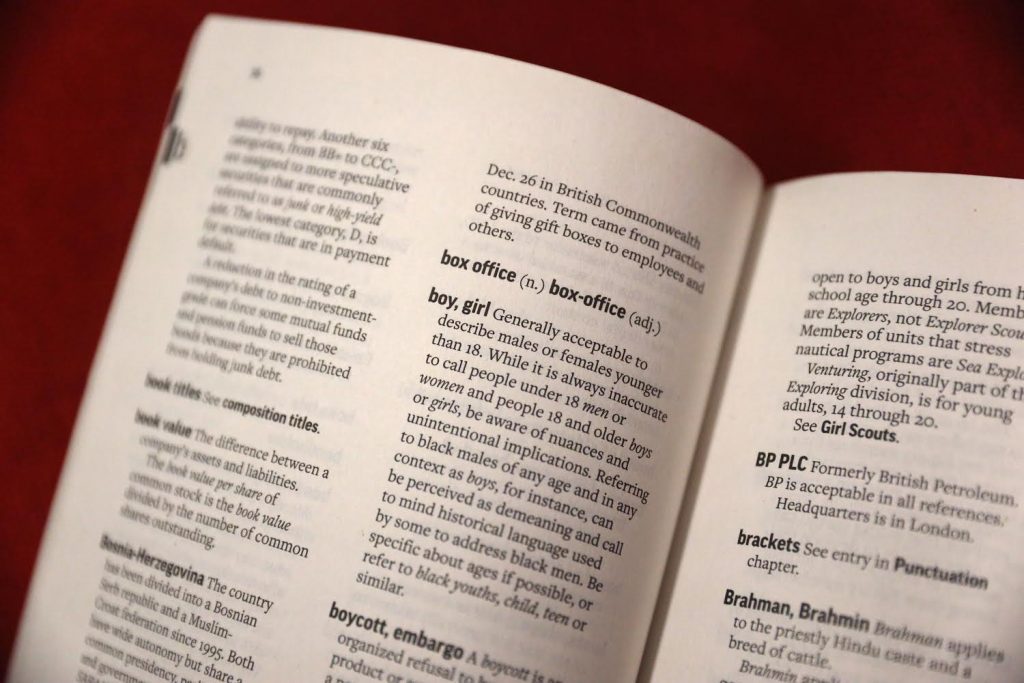

Negassi pointed out that it’s important to describe those who have experienced sexual assaults as survivors, not victims.

Steiner said that it is imperative that journalists are taught new skills to cover #MeToo.

Steiner questioned, “How do you establish an attitude of caring and empathy and give people the time and space they need to tell their stories?”

These are not the typical investigative reporting skills, but she said journalists need to know how to talk to both survivors and perpetrators.

In the same way, the panel also discussed the need for student journalists and young journalists to be prepared in case they are harassed or witness harassment.

Panel 2: Gender at Work: Overcoming Bias in the Newsroom

Michelle Ferrier, Jon Sawyer and Christina Kahrl

- Lindsay Palmer (moderator), assistant professor, School of Journalism & Mass Communication, UW-Madison

- Michelle Ferrier, dean of the School of Journalism & Graphic Communication at Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University, founder of TrollBusters.com

- Christina Kahrl, senior editor for MLB coverage at ESPN

- Jon Sawyer, executive director of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting

Three panelists spoke on their different experiences in the field of journalism as a black woman, a transgender woman and a white man.

Ferrier discussed being one of a few people of color in the newsroom.

She found herself arguing with her own writers on the desk about diverse representations in stories they covered. And she discussed the challenges of there being so few people of color in the newsroom.

“I was terrified for the nights that I wasn’t working because of what my colleagues would do – worried about them not representing the people of color in the community,” Ferrier said.

Christina Kahrl shared her experience of working at ESPN before and after transitioning, saying that she has experience “on both sides of the gender divide.”

After transitioning, someone sat next to her in the press box at a game and asked if she needed help learning to keep score. She found it validating to be acknowledged as a woman, but extremely upsetting to see this gendered bias.

Jon Sawyer began his remarks by saying, “I’m the guy that lived his career in unconscious enjoyment of white male privilege.”

The #MeToo movement helped him realize how much he doesn’t see, as a white man.

“It was a reminder of how different the world can look if you’re a man, woman or person of color.” He continued, “You cannot assume that the dynamic that you’re sharing is the same.”

Panel 3: Real World Solutions: Moving Forward with Equity & Integrity

Panel 3: Real World Solutions: Moving Forward with Equity & Integrity

Jill Geisler, Lindsay Palmer, Sharif Durhams, Susan Ramsett and Traci Schweikert

- Jill Geisler (moderator), Bill Plante Chair in Leadership & Media Integrity, Loyola University Chicago and Freedom Forum Institute Fellow in Women’s Leadership

- Sharif Durhams, senior editor, CNN

- Lindsay Palmer, assistant professor, School of Journalism & Mass Communication, UW-Madison

- Susan Ramsett, general manager, KWQC TV-6

- Traci Schweikert, vice president of human resources, POLITICO

Geisler began by saying that the standard harassment training used by news organizations has not demonstrated effectiveness, except at reducing liability in lawsuits.

Schweikert said, “Early in my career, I was taught that being creepy isn’t against the law.”

She continued to say that we shouldn’t just consider what’s against the law because then we miss the chance to catch things early. You want to make sure that there is a level of understanding that can be applied to a day-to-day scenario.

At Politico, human resources staff meet with other Politico staff members at their corresponding level to discuss the culture and expectations.

Durhams noted that everyone has worked in a newsroom where a macho culture is celebrated. He said there is work to be done in the largest newsrooms in the country and in the smaller, regional newsrooms.

Ramsett also discussed the whisper circle that exists in newsrooms. It was a circle of women who would warn each other about predators in the newsroom.

She said that she knew so many people who left the business because of how they were treated.

“Even if I couldn’t make a change to the past, I wanted to make a difference moving forward,” she said.

Geisler also presented information on the Freedom Forum’s Power Shift Project and its Workplace Integrity Training, which aims to eliminate sexual harassment from the news industry.

The Center for Journalism Ethics encourages the highest standards in journalism ethics worldwide. We foster vigorous debate about ethical practices in journalism and provide a resource for producers, consumers and students of journalism. Sign up for our quarterly newsletter here.